By John L. Turner

“I prefer winter and fall, when you feel the bone structure of the landscape — the loneliness of it; the dead feeling of winter. Something waits beneath it, the whole story doesn’t show.” — Andrew Wyeth

Not sure if planetary scientists can explain why, when the earth was forming, it became tilted about 23.5 degrees off a perfect perpendicular axis to its orbital plane around the Sun. However, they can offer an unequivocal statement of fact that this planetary quirk is the reason for the portfolio of seasons we enjoy. And now, as has been often true for more than four and one-half billion years, when the planetary axis that runs through the North Pole points away from the Sun, the Northern Hemisphere receives weaker, more obtuse rays of sunshine, resulting in the colder temperatures of winter.

Today, as they have for millenia, countless number of plants and animals have responded in their own species-specific ways to survive this most challenging of seasons.

A discussion about the pervasive effects of winter on nature cannot happen without talking about another word that begins with the letter “w” and ends in an “r” — water. Water, or more particularly the fact that it becomes ice at 32 degrees, has had profound impacts in shaping the response of organisms to winter. As water becomes ice, it’s no longer available to plants, making winter, in effect, a five to six month long drought. The response of deciduous trees to no available water? To shed their leaves that are water loss structures and become dormant. How do evergreen or coniferous trees, which obviously keep their leaves, tolerate the winter’s loss of available water? Their small leaves with waxy coatings are highly effective at retarding water loss. They simply use little water in the winter.

How else does ice affect species? Ducks, geese and swans that depend upon open freshwater ponds and lakes to feed need to move in the event their ponds freeze over. Same with kingfishers and other fish-eating birds. This “freezing over” occurs because ice, by rare virtue of being less dense than liquid water, floats on the surface of the surface of the pond or lake, rather than freezing at the bottom which would happen if ice were denser than water, which is the norm with so many other liquids. This unusual, almost unique, attribute — of solid water (ice) being lighter than liquid water — has played a hard to overstate role in allowing for life on earth to evolve and flourish, for if ice were denser the entire waterbody would freeze solid to the detriment of everything living in it.

Unlike immobile species such as trees, mobile species (i.e. animals that fly!) adapt to winter by simply leaving it behind, winging to warmer climates where they can continue to feed (some species living a perpetual summer existence!). Such is the case with dozens of bird, bat, and insect species that migrate vast distances to find climates and associated food supplies to their liking.

For example, ospreys depart from northern latitudes because the fish they depend upon are unavailable, either because they can’t access them due to ice or because salt-water fish move into deeper water where they cannot be caught, forcing ospreys to move to habitats within climates where food is available. Insect-eating songbirds move off too but in their case because of the disappearance of available insects.

Mobile species that don’t migrate employ a variety of other strategies to survive the winter. A perhaps most well-known — but relatively rare — strategy is hibernation. Hibernating mammals species adapt to winter by so reducing their energy and water needs they can tide over from autumn to spring.

The woodchuck (aka groundhog) is the best known hibernator. Curled in an underground den, a hibernating woodchuck’s heart beat drops from about 100 beats per minute to four to five and its body temperature more than half, from about 99 degrees to 38-40 degrees. Bats that don’t leave for warmer climates also hibernate. All hibernating species depend upon stores of fat, built up from continued feeding in the autumn, as the energy source to make it through winter.

Just below hibernation is torpor, a physiological state in which the animal’s metabolism, heart and breathing rates are reduced but which still allows it to be alert enough to react to danger. Chipmunks (and bears) are well known examples and speaking of chipmunks — they illustrate another common practice of many animals to make it through the winter — storing up food in winter larder. Beavers do the same by bringing leaf-laden branches underwater, a wet refrigerator of sorts, where food is safely ensconced.

Regulated hypothermia is yet another adaptation to surviving winter. In this case, the animal reduces its temperature while sleeping, enabling it to reduce the amount of heat lost to the air overnight. Black-capped chickadees are a well-known example. During the winter chickadees drop their temperature each night from about 108 degrees to the mid-90’s by employing this practice. They also seek sheltered places like tree cavities (another reason to let dead trees stand if they pose no safety risk) and dense vegetation where they can stay warmer.

Cold blooded animals such as reptiles and amphibians make it through winter by experiencing their own form of hibernation — an activity known as brumation. Like with warm blooded animals, brumating reptiles and amphibians significantly reduce their heart, breathing and general metabolic rates. Some species, like diamondback terrapins, are spared the full brunt of winter by brumating in the muddy bottoms of bays, harbors, and river mouths where the temperature never drops below freezing. Not so with the wood frog, a wide ranging amphibian that in March emerges to explosively breed in woodland vernal pools around Long Island.

Wood frogs are known to freeze solid, becoming ‘frogsicles’ during the winter and getting as close as a live animal can get to being dead. As autumn slides into winter, wood frogs undergo a several-step physiological process whereby water is pulled out of cells and is stored between them. This movement of water from inside the cell to sites between the cells occurs because water stored within the cell, if frozen, would form sharp ice crystals, likely puncturing cell membranes, thereby destroying the cell.

The frog’s metabolism, breathing, and heartbeat stop and the frog remains in a state of animated suspension for many weeks. Come the Spring though, and this very dead looking frog slowly comes back to life, none worse for the wear. It becomes active and vibrant, soon filling small wetlands with its quacking duck calls.

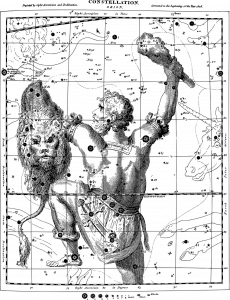

For the lover of nature and the outdoors there are gifts of winter: clear night skies; falling snow and geometric snowflakes; frost patterns on windows; sledding and hot chocolate (or for some adults mulled apple cider spiked with a little spirit!); no leaves to hide bird nests or tree buds, like those of American Beech, which Henry David Thoreau called “the spears of Spring”; the dried stalks of countless wildflowers; the “pen and ink” quality of landscapes; the presence of snowy owls and snow buntings at the beach; or the arrival of many types of ducks and geese. Winter is not an absence of summer; it is a season complete and whole to itself.

Perhaps this article won’t serve to change your thinking if you’re among the crowd of people who find winter to be their least favorite season. Still, winter illustrates so clearly and compellingly the fine-tuned lives of so many plants and animals, each unique to this time of cold, lives that have developed, over eons of time, countless strategies to make it through the unrelenting cold and sparse food supplies of the winter season.

A resident of Setauket, John Turner is conservation chair of the Four Harbors Audubon Society, author of “Exploring the Other Island: A Seasonal Nature Guide to Long Island” and president of Alula Birding & Natural History Tours.

When I last looked at the Milky Way, a couple of days ago, it reminded me of our most humble place in the universal ethos and of a famous line by the poet Robinson Jeffers: “There is nothing like astronomy to pull the stuff out of man, His stupid dreams and red-rooster importance: let him count the star-swirls”.

When I last looked at the Milky Way, a couple of days ago, it reminded me of our most humble place in the universal ethos and of a famous line by the poet Robinson Jeffers: “There is nothing like astronomy to pull the stuff out of man, His stupid dreams and red-rooster importance: let him count the star-swirls”.

For example, two scientists discussing otter biology need to know what otter species they’re talking about. Is it the Sea Otter (Enhydra lutris)? Or maybe the River Otter (Lontra canadensis) or Asian Small-clawed Otter (Aonyx cinereus)? How about Giant River Otter, (Pteronura brasiliensis), European Otter (Lutra lutra) or any other of the thirteen species of otters found in the world. In discussing some aspect of otter ecology or biology, just mentioning “otter” may not be sufficient to provide the level of specificity or accuracy needed. Researchers need to know they’re both talking about the same species of otter. Or bacteria. Or slime mold. Or many other species that can affect us.

For example, two scientists discussing otter biology need to know what otter species they’re talking about. Is it the Sea Otter (Enhydra lutris)? Or maybe the River Otter (Lontra canadensis) or Asian Small-clawed Otter (Aonyx cinereus)? How about Giant River Otter, (Pteronura brasiliensis), European Otter (Lutra lutra) or any other of the thirteen species of otters found in the world. In discussing some aspect of otter ecology or biology, just mentioning “otter” may not be sufficient to provide the level of specificity or accuracy needed. Researchers need to know they’re both talking about the same species of otter. Or bacteria. Or slime mold. Or many other species that can affect us.