By Matthew Kearns, DVM

Cutaneous mast cell tumors are the most common skin tumor in dogs (estimated to be at least 20 percent of all skin tumors in dogs), and one of the most commonly encountered tumors in veterinary medicine. Mast cell tumors can be quite aggressive and cause multiple symptoms (all bad). Where do they come from? What do they do? How do we treat them?

Cutaneous mast cell tumors are malignant skin tumors made up of mast cells, cells normally found in tissues throughout the body. Mast cells contain primarily histamine, a vasoactive protein (a chemical that affects the diameter and tone of blood vessels) and are responsible for allergic reactions.

Small amounts of histamine cause swelling, itching and redness of the skin. Large amounts of histamine trigger constriction of the airway, dilation of the vessels and an unsafe drop in blood pressure (anaphylaxis).

Mast cell tumors develop most commonly in mixed-breed dogs. However, boxers, Boston terriers, Labrador retrievers, schnauzers and beagles are pure breeds that are at higher risk. If you have one of these breeds and you see a lump on your dog’s skin, bring it to your veterinarian’s attention as soon as possible.

Diagnosis of cutaneous mast cell tumors is relatively straightforward and minimally invasive with a procedure called a fine needle aspirate and cytology. This involves obtaining a sample of cells with a needle attached to an empty syringe and sending the sample to a laboratory for evaluation by a veterinary pathologist. Once diagnosed, the best treatment is surgical removal, and the surgery does have to be somewhat aggressive by requiring wide margins.

“Wide margins” refers to taking a certain amount of healthy tissue around and below the tumor, as well as the tumor itself. This poses the challenge of closing the “hole” you leave behind.

Why do we take such large and aggressive margins? Mast cell tumors are graded as one, two or three based on aggressiveness, and it is impossible to tell from a fine needle aspiration anything beyond the diagnosis of mast cell tumor. Previous studies have stated that certain margins, both width and depth, help ensure you get all of the tumor the first time.

What do we do for patients that may be too old or debilitated for anesthesia/surgery, or the location of the tumor makes it impossible to remove fully with surgery? There are options such as chemotherapy, radiation and even injections directly into the tumor. All these alternative protocols help, and a small percentage actually completely resolve, or remove the tumor.

If you see a lump pop up on your dog’s skin (especially if you notice it pops up quickly), bring it to your veterinarian’s attention immediately.

Dr. Kearns practices veterinary medicine from his Port Jefferson office and is pictured with his son Matthew and his dog Jasmine.

Here we are, getting ready for another great summer on Long Island. This article will address preventative care and safety issues for the best summer ever!

Here we are, getting ready for another great summer on Long Island. This article will address preventative care and safety issues for the best summer ever!

My last column introduced the seasonal allergies that our pets can suffer from, also known as atopic dermatitis. This second part of the two-part article focuses more on the treatment of atopic dermatitis. The treatments we will discuss only focus on systemic medications. It does not include supplements, topical creams/powders/sprays, medicated shampoos/conditioners, etc. I’ll make sure to cover that in the future.

My last column introduced the seasonal allergies that our pets can suffer from, also known as atopic dermatitis. This second part of the two-part article focuses more on the treatment of atopic dermatitis. The treatments we will discuss only focus on systemic medications. It does not include supplements, topical creams/powders/sprays, medicated shampoos/conditioners, etc. I’ll make sure to cover that in the future. Corticosteroids, glucocorticoids, or “steroids,” as they are sometimes referred to, are all cortisone derivatives. Systemic cortisone medications are prescription only. However, corticosteroids are inexpensive and very effective at treating atopic diseases. They block the production of all cytokines (mediators of inflammation) and, if it wasn’t for the side effects, would be a magic bullet. Short-term use is relatively safe and very beneficial. Side effects include drinking/urinating more, eating more and panting.

Corticosteroids, glucocorticoids, or “steroids,” as they are sometimes referred to, are all cortisone derivatives. Systemic cortisone medications are prescription only. However, corticosteroids are inexpensive and very effective at treating atopic diseases. They block the production of all cytokines (mediators of inflammation) and, if it wasn’t for the side effects, would be a magic bullet. Short-term use is relatively safe and very beneficial. Side effects include drinking/urinating more, eating more and panting.

Who knows when the next winter “bomb-cyclone” followed by an arctic cold front will hit Long Island. Here are a few important facts and tips to help our pets get through another winter:

Who knows when the next winter “bomb-cyclone” followed by an arctic cold front will hit Long Island. Here are a few important facts and tips to help our pets get through another winter: Arthritis affects older pets more commonly but can affect pets of any age with an arthritic condition. Cold weather will make it more difficult for arthritic pets to get around and icy, slick surfaces make it more difficult to get traction. Care should be taken when going up or down stairs and on slick surfaces. Boots, slings and orthopedic beds can be purchased from pet stores, online or through catalogs. These products will help our pets get a better grip on slick surfaces or icy surfaces and sleep better at night to protect aging bones and joints.

Arthritis affects older pets more commonly but can affect pets of any age with an arthritic condition. Cold weather will make it more difficult for arthritic pets to get around and icy, slick surfaces make it more difficult to get traction. Care should be taken when going up or down stairs and on slick surfaces. Boots, slings and orthopedic beds can be purchased from pet stores, online or through catalogs. These products will help our pets get a better grip on slick surfaces or icy surfaces and sleep better at night to protect aging bones and joints.

I had a classmate in veterinary school who simply described his cat as “good for the head.” What he meant by that statement was when the stress of classes and studying became too much he could always count on his cat to ease the burden. Well, science is backing up this claim. Having a pet in your life can be good for the head and the body.

I had a classmate in veterinary school who simply described his cat as “good for the head.” What he meant by that statement was when the stress of classes and studying became too much he could always count on his cat to ease the burden. Well, science is backing up this claim. Having a pet in your life can be good for the head and the body.

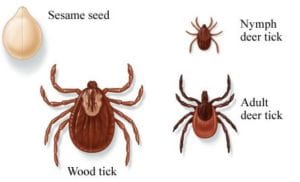

I commonly get the question, “What month can I stop using tick preventatives?” My answer is always, “That depends.” It used to be that somewhere around late October/November until late March/early April one could stop using flea and tick preventatives. However, with changing climate conditions and parasite adaptation this is no longer true.

I commonly get the question, “What month can I stop using tick preventatives?” My answer is always, “That depends.” It used to be that somewhere around late October/November until late March/early April one could stop using flea and tick preventatives. However, with changing climate conditions and parasite adaptation this is no longer true. To kill a tick temperatures must be consistently below 10°F for many days in a row. If the tick is able to bury itself in the vegetation below a layer of snow, even below 10 degrees may not kill them. It is pretty routine even in January to have one or two days that are in the 20s during the day, dropping to the teens or single digits at night followed by a few days in the 50s.

To kill a tick temperatures must be consistently below 10°F for many days in a row. If the tick is able to bury itself in the vegetation below a layer of snow, even below 10 degrees may not kill them. It is pretty routine even in January to have one or two days that are in the 20s during the day, dropping to the teens or single digits at night followed by a few days in the 50s.