By Daniel Dunaief

Convenience can come at a cost, even in medicine. When it comes to a heart procedure called cardiac artery bypass surgery, that cost could make a difference in the outcome for the patient.

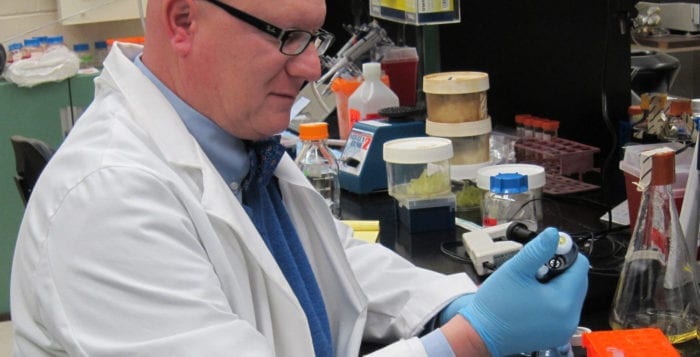

Annie Laurie W. Shroyer, vice chair for research and professor in the Department of Surgery at Stony Brook University School of Medicine, and Thomas Bilfinger, a professor of surgery in the Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery at SBU, found that the mortality and major morbidity rates were lower for patients of surgeons performing procedures at a single center compared to those performing procedures at more than one center.

Among physicians who operated at two or more hospitals, these surgeons performed better at their home hospital than at a secondary center.

They’ve published their findings in the Annals of Thoracic Surgery. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons identified the article as the Continuing Medical Education article for the month. The article will provide a much more in-depth learning experience to a subgroup of the journal’s subscribers who seek Continuing Medical Education credits. This, Shroyer explained, will make it more likely that cardiac surgeons will read it thoroughly and discuss it.

“We believe that, based on the results, particularly complex coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) procedures may have a better outcome at bigger institutions,” Bilfinger explained in an email. Mortality for these procedures overall in the United States is low and the analysis is about differences of a few tenths of a percent, which becomes statistically significant due to the low number.

The central issue, Bilfinger said, is whether “the mother ship does better or worse than the satellite. Decision making about centralizing versus a de-centralized approach seems to be less driven by outcomes and rather by business decisions in many circumstances. The study adds some subjective data to this discussion.”

Using a measure called observed-to-expected mortality ratios based on the health of the patient and risks of the procedure, the ratio for multicenter surgeons was higher for the satellite facilities compared to their home facilities. The ratios were 1.17 for surgeons operating at satellite facilities versus 1.01 for multicenter surgeons performing the procedure at their home hospital.

The volume of surgeries is a complicated issue, Bilfinger cautioned. “There are very well-performing smaller volume places throughout the country,” he explained in an email. “It involves dedication to the procedures from admission to discharge.”

Assuming the surgeon is just as effective in different hospitals, which is “open to discussion,” any observed difference could be attributable to the system, Bilfinger explained. Measuring the effectiveness of the participants in the process, including nurses, anesthesiologists and orderlies, is a question for ongoing research, he continued.

Joseph Carey, a cardiovascular and thoracic surgeon in Torrance, California, conducted a study based on information from California about a decade ago. In an email, Carey suggested that “you pay a price in quality working in unfamiliar conditions and I believe hospital managers do not want their surgeons traveling about.” He added that this paper “is an important reminder” of this.

Carey added that hospital systems and the makeup of the “heart team” may also be important to the outcome of a surgery.

Future research, which Shroyer plans to conduct, will evaluate other factors, such as patient risk, processes and structures of care, that impact cardiac surgical outcomes.

Other researchers could extend this study, which compares the quality of care for surgeons who work at single sites and multisites, to other areas of medical care, enabling hospital networks, insurance companies and patients to make informed risk-based decisions prior to approving difficult procedures.

The challenge, however, with similar studies for other conditions, is in finding national information. “This is the best documented group of procedures there is in the country,” Bilfinger said. For a procedure like back surgery, it might be difficult to come up with a comparable study, although Bilfinger said he “suspects strongly that this is a very similar relationship.”

Shroyer and Bilfinger will extend their work to another cardiothoracic operation. They have submitted a proposal to the Society of Thoracic Surgeons to start a parallel project to look at the difference in risk-adjusted outcomes for mitral valve procedures that compare single-center versus multicenter surgeons. The diversity of procedures may need to be considered in comparing single and multicenter surgeons.

Bilfinger said he recognizes that some doctors and hospital networks may find these conclusions disconcerting. It may give them pause in the internal discussion about value added by new satellites in any system, he explained. “This is worth a public debate. This is one of these aspects of modern health care that the consumer is not aware of.” The average consumer may not put too much emphasis on this, although the sophisticated consumer on Long Island may change or make decisions based on this type of information, he said.

Shroyer and Bilfinger, who have worked on the same floor at the Health Sciences Center since Shroyer arrived from Colorado in 2007, decided to collaborate on this project after a discussion during lunch. The duo were eating at SBU’s Simons Center Café when they were discussing the differences in outcomes for single and multicenter surgical procedures. They submitted a request to access the National Adult Cardiac Surgery Database in 2014 to the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

For patients who are going to have a cardiac surgical procedure, Shroyer recommends that people choose their surgeon and surgery center “wisely.” She recommends researching the surgeons and their corresponding center’s bypass specific outcomes. She highlights two publicly available resources, which are Adult Cardiac Surgery Database Public Reporting|STS Public Reporting Online and Doctor Ratings — Consumer Reports.

Shroyer cautions that these ratings are somewhat outdated, so she suggests patients ask their surgeons directly about their more recent outcomes. She would also recommend contacting patients.

After conducting this study, Shroyer believes it would likely help patients if they searched for doctors who only perform bypass procedures at a single hospital. She also believes it is important for patients to consider surgeon-specific and center-specific risk-adjusted outcomes.

Ultimately, she said, the decision about a surgeon and a site for surgery is an important one that patients should make based on the likelihood of the best outcome.

“Patients should research their cardiac surgeon-hospital decision even more carefully than if they were buying a new home or a new car,” she explained in an email. “Their future health lies in their cardiac surgeon’s hands.”