By Daniel Dunaief

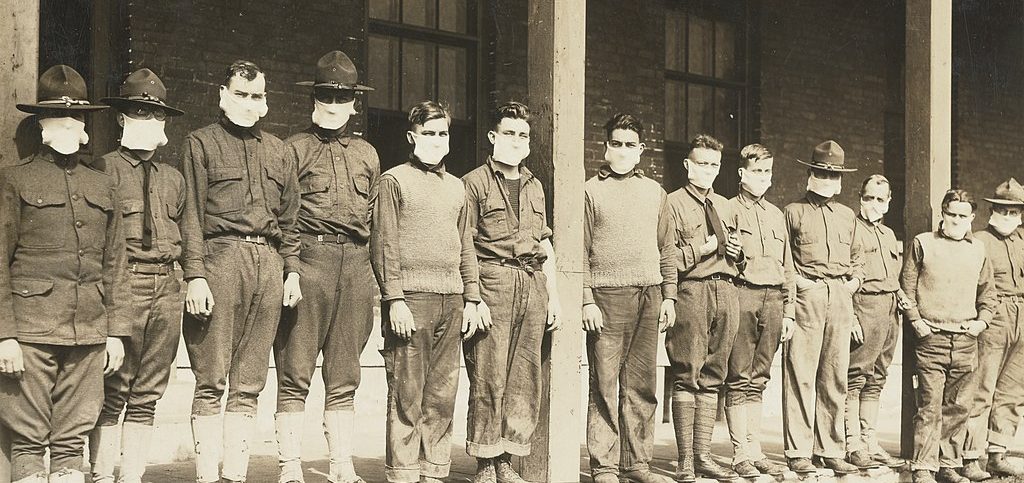

At the end of World War I, Spanish Influenza caused the world to focus on the same kinds of measures that people have been using to protect themselves, including wearing masks and social distancing.

Back then, pharmaceutical companies couldn’t produce vaccines and boosters for the H1N1 flu virus which killed 50 million people worldwide, including 650,000 people in the United States.

Public domain photo

History professors at Stony Brook University described a decidedly different period over 100 years ago and the reaction by the American people to the public health crisis.

The armistice to end the war was signed in the middle of the pandemic, said Nancy Tomes, distinguished professor in the Department of History at Stony Brook University.

“Our noble dough boys were coming back after having saved Western Civilization,” Tomes said. There was no finger to point to blame someone for the coming hardship. The American public recognized that this was an “ailment our brave boys brought home. It’s your obligation to take care of these soldiers.”

People who didn’t do their part to help heal members of the military and reduce the threat were considered “slackers.” When public health officials in New York asked workers to stagger the times they took the subway, people “were not supposed to kick up a fuss because this is war,” Tomes said.

During the Spanish Influenza, people didn’t express partisan politics about public health issues.“The idea was that there’s an epidemic and it’s all hands-on deck,” she added.

Contrast that with modern times, when an anti-federal government ideology has been developing for decades, said Paul Kelton, professor and Gardiner chair in American History at Stony Brook.

“That’s been brewing since the 1980s,” Kelton said. The COVID pandemic happened at a time when this distrust toward the federal government “reached its peak.” Today, “we have a national media culture where we focus on the federal government” and, at the same time, the country has an anti-federal government ideology that’s animating a large portion of the American population,” he said.

Kelton, whose expertise includes the study of Native American history, suggested that several tribes have embraced the opportunity to get the vaccine, in part because of the encouraging response among tribe leaders.

The Navajo, for example, who have a well-earned skepticism toward the federal government, have a high rate of vaccination because the tribal government has taken charge of this public health effort.

“When people are empowered at the state and local level, rather than the federal government coming in and doing it, it makes a difference,” Kelton said.

Indeed, the communities that have resisted vaccines and public health measures during the current COVID crisis include areas with high rural white populations.

To be sure, historians recognize that the specifics of each pandemic, from the source of the public health threat to the political and cultural backdrop against which the threat occurs, vary widely.

Recalling a saying in the field of public health, Kelton said, “if you’ve seen one pandemic, you’ve seen one pandemic.” That suggests that the lessons or experiences amid any single public health threat don’t necessarily apply to another, particularly if the mode of transmission, the symptoms or the severity of the threat are all different.

“The lesson from history is to expect the unexpected when you’re dealing with germs,” said Kelton. “Novel germs are hitting populations in different circumstances. We are living in different conditions than in the past.”

What pandemics generally do, Kelton said, is expose fissures in society.

Part of what the study of other pandemics suggests is the need for opportunities to live healthier lives among those who are impoverished or are feeling disenfranchised.

“If nothing changes and health care access [remains as it is],we are going to repeat that again,” Kelton said.

Basic access to better nutrition can help fight the next pandemic, reducing the disproportionate toll some people face amid a public health threat, he said.

“Things like making sure that homeless people can get into a homeless shelter and not infect each other, the nuts and bolts of keeping people healthy, we neglected,” added Tomes.