By Beverly C. Tyler

In “Two Years Before the Mast,” R.H. Dana Jr. wrote in 1840, “However much I was affected by the beauty of the sea, the bright stars, and the clouds driven swiftly over them, I could not but remember that I was separating myself from all the social and intellectual enjoyments of life.”

I spent a week this April as a crew member on the training barque Picton Castle. This square-rigged sailing ship is similar in size and function to the Mary and Louisa that my great-grand-aunt Mary Swift Jones sailed on to China and Japan in 1858.

I wanted to experience, in a small way, what my Aunt Mary experienced and observed as the wife of Captain Benjamin Jones on their three-year voyage. I know, of course, that a week on the Picton Castle is not really comparable to an almost round-the-world voyage, but I also knew that it would have to do. I came away from the experience with a new understanding of life aboard one of the many tall ships that travel the world today with crews learning sail handling and working together to achieve the goal of maintaining a historic ship under sail.

Having visited the Picton Castle in Lunenburg, Nova Scotia; Auckland, New Zealand; and Greenport, Long Island, between 2011 and 2015, I felt the romance of the old sailing ship and hoped I would have a chance to sail on her. I thought that seeing and feeling her with full sails moving almost silently through the water would be the part I would enjoy the most.

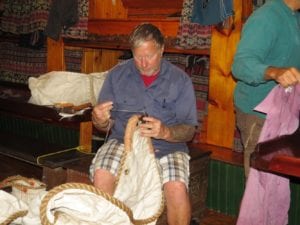

After a week on board, handling lines under close supervision and doing all the necessary chores that keep this tall ship functioning, I came away with an appreciation of the crew members with whom I worked. This is a hard-working and dedicated group from the officers and lead seamen to the advanced trainees who together instructed the new trainees in the basics of safety, line and sail handling and the myriad of jobs that have to be done every day. One I became fairly good at — whipping the bitter ends of lines to finish them off and prevent unraveling.

My first days on duty I shadowed one of the trainees who had been on the Picton Castle for a year, including a winter trip through the North Atlantic when ice covered much of the running rigging, making it very difficult to move the lines through the blocks that control the sails. There were no beginning trainees on this leg of the voyages to and from Lunenburg, the home and training port for most of the regular crew, as they had to function quickly and decisively under severe conditions.

I asked my instructor why he chose this type of work. He told me that he had been boating along the Atlantic coast with his grandfather since he was a child and growing up had done all the things that were expected of him — an education, a degree and a resulting steady job. By the time he was 30, he realized he needed a change and the sea was calling him back. He said he has found what he wants to do with his life — he loves to be at sea and he knows he is good at it. He has picked up the routine and the skills quickly and is proud of the work he is doing on Picton Castle, working the deck and teaching new trainees.

On watch we worked lookout and helm together as well as working lines from the complicated array of gear — lines and equipment — that controls the spars and sails. We were fortunate to have our watch group of 11 assigned to the 4 to 8 watch, both a.m. and p.m., on the trip from Galveston, Texas, to Pensacola, Florida. My instructor noted that this was the best watch this time of year since we are on duty for both sunrise and sunset. On the first 4 to 8 a.m. watch after two days of rain, wind and 4- to 6-foot seas, we were in the Gulf of Mexico 60 miles from the nearest land.

The sky was clear, and the stars were brighter than any sky I had seen since crossing the Atlantic in the U.S. Navy in the late 1950s. The Milky Way shone brightly, and there were so many stars it would be difficult to add more stars between the ones I could see. It made me realize how important the sky was to the ancient civilizations who observed it every night that was not overcast. All the various constellations were easily identified along with the planets.

After a week on the Picton Castle, I had to reevaluate what I had gained from the experience. The most important to me was the people I met, especially the officers and crew who spend countless hours instructing and reinstructing us no matter how long it took and how many times they had to go over the same information. My fellow new trainees, many of whom became friends for a week, were dedicated to learning and the hard work that went with it. Next in lasting importance and wonder was the night sky and the changeover from dusk to dawn in the morning as the crescent moon rose followed by the sun. Next was this beautiful sailing ship itself that inspired all of us with its abilities, functionality and beauty.

Beverly C. Tyler is Three Village Historical Society historian and author of books available from the society at 93 North Country Road, Setauket. For more information, call 631-751-3730 or visit www.tvhs.org.