Reviewed by Jeffrey Sanzel

“The reality of the rumrunning business is a lot darker than local memory paints it.” In the fascinating book, Rumrunning in Suffolk County: Tales from Liquor Island (The History Press), author Amy Kasuga Folk resists the whimsy and nostalgia often employed when writing about the Prohibition era. Instead, she offers a focused, detailed account, thoroughly researched and rich in detail.

Folk opens with a concise history of nineteenth-century alcohol consumption, the rise of the temperance movement, and how it connected to anti-immigrant sentiment. She points to the bias against immigrants and addresses the “nativist prejudice link[ing] the new arrivals with drunkenness.” Citing this fearmongering tips the book from an exclusively historical perspective to a sociological angle.

The creation of the Volstead Act banned the sale of alcohol, with Prohibition coming into force on January 17, 1920. Folk presents an informative overview of the history of drinking and liquor sources during the 1920s. Much of the book focuses on the change in the criminal element. Prohibition transformed street gangs dominating small areas into more dangerous organized crime. The time saw the rise of figures like Arnold Rothstein, Dutch Schultz, Lucky Luciano, Meyer Lansky, and Bugsy Siegel.

Folk has a strong sense of the business elements of rumrunning:

To give you an idea of how a big of a business this was, the gang on average paid $200 a week to one hundred employees when the average store clerk took home $25 a week, and they paid $100,000 a week in graft to police, federal agents and city and court officials. Despite these expenses, the gang still took in an estimated net profit of $12 million a year from the business.

At a time when a consumer could purchase a dozen oranges for twenty-five cents, the figures are astronomical.

Cargo ships would anchor just outside the territorial line of United States waters; then, small, fast boats would claim the liquor and take it back to shore. Thus, “rumrunning” was born. Shortwave radios were common—quoting coded messages and describing inventory, orders, sales, and other details. Messages were even broadcast through commercial radio stations.

The book chronicles year-by-year, from 1921 through 1932. Violence on both sides of the law was commonplace. From fisherman hiding bottles in their catches to potato trucks concealing cases of illicit whiskey, Folk shows the intersection of day-to-day life with the precarious, dangerous business that made “Long Island, which is also termed Liquor Island … the wettest spot in the entire country.” (County Review, February 1, 1924)

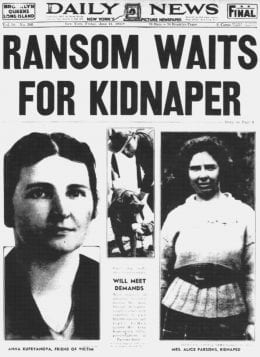

In a detailed exploration, Folk mentions judges, attorneys, law enforcement agents, and a full range of transgressors. She has a complete command of the large cast of characters, the hundreds of boats, and other vehicles, along with the events surrounding them. Anecdotes include raids, trials, missteps, and hundreds of thousands of dollars and millions of gallons of liquor. There are storms and drownings, shootouts, and collateral damage. From Southold to Huntington Harbor, the accounts tell of the clash of lawmen and gunmen. The author complements the text with a wide range of period photos.

The book is not without a touch of humor, as in this account of April 1927:

In an effort to move faster by lightening their load, a rumrunner being chased by the Coast Guard had thrown case after case of scotch overboard. The cases riding the waves were estimated to be fifteen to twenty miles out, but they were floating towards the shore. Guardsmen from the Quogue station spotted the first crate floating inland, and by two o’clock in the afternoon, it had become a race—all the locals turned out determined to get a slice of the bounty floating toward their community before the government swept it all up.

“One of the problems of enforcing Prohibition was the revolving door of justice. The rumrunners and bootleggers had the money and the ability to easily make bail and walk away from the charges against them.” Sometimes, they would move their cargo when agents were testifying in court. In addition, the book addresses widespread government corruption as agents were basically “untouchable.”

Case-in-point: the head of the industrial alcohol inspection section of the Prohibition office in New York, Major E.C. Schroeder, went to jail for blackmail. But the flip side was that the government agencies, especially the Coast Guard, were woefully understaffed to take on the mammoth problem. Most actions were based on well-grounded evidence and experience.

Great fear existed among civilians. Getting misidentified as a rumrunner or being caught in the crossfire between bootleggers and the Coast Guard was not uncommon. Hijackings of boats, people held prisoner, low-level criminals turned informants winding up with bullets in their foreheads, all composed elements of the time. The events and incidents were so complicated that even the newspapers gave conflicting reports.

For the casual reader or the historian, Rumrunning in Suffolk County provides an excellent introduction and a detailed account of the Prohibition era in the eastern Long Island community

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Author Amy Kasuga Folk is the manager of collections for the Oysterponds Historical Society, as well as the manager of collections for the Southold Historical Society and the town historian for Southold. Folk is also the past president of the Long Island Museum Association and the Region 2 co-chair of the Association of Public Historians. She is the coauthor of several award-winning books focusing on the history of Southold. Pick up a copy of the book at Amazon.com, or BarnesandNoble.com.