Water, water everywhere and several scientists want to make sure there are plenty of drops to drink.

Christopher Gobler, director of the New York State Center for Clean Water Technology, and Arjun Venkatesan, the CCWT’s associate director for Drinking Water Initiatives, recently published two studies in which they highlighted how their efforts to reduce nitrogen also cut back on 1,4 dioxane, a likely carcinogen.

Gobler, who is also endowed chair of Coastal Ecology and Conservation at Stony Brook University’s School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences, is leading a center whose mission is to solve the nitrogen overloading crisis in Long Island’s groundwater and surface water by developing alternative onsite septic systems.

Nitrogen, which comes from a host of sources including fertilizer, creates the kind of conditions that lead to algal blooms, which can and have closed beaches around Long Island. Nitrogen also harms seagrass meadows and can cause the collapse of shellfisheries like clams and scallops.

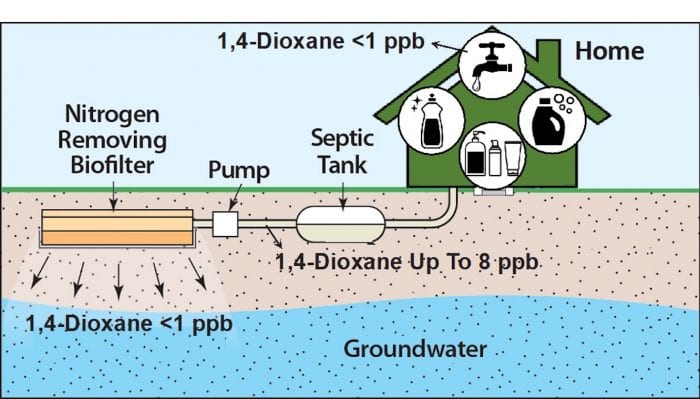

In the meantime, 1,4 dioxane, which is a potential health threat in Suffolk and Nassau counties, comes from household products ranging from shampoos to cleaning products and detergents. Manufacturing on Long Island in prior decades contributed to the increase in its prevalence in water sources.

Indeed, recent studies from the center showed “very high levels of 1,4 dioxane have been detected in our groundwater,” Venkatesan said in a recent press conference.

The chemical doesn’t easily degrade, conventional wastewater treatment doesn’t remote it, and household and personal care products contribute to its prevalence in the area.

A one-year study “confirmed this suspicion,” Venkatesan said. “The level of 1,4 dioxane in a septic effluent is, on average, 10 times higher than tap water levels.”

This finding is “important” and suggests that the use of these products can ultimately end up polluting groundwater, Venkatesan continued.

At the same time, the increasing population on Long Island has contributed to a rise in the concentration of nitrogen in groundwater, Gobler added during the press conference.

The center hoped to create a septic-enhancing system that met a 10, 20, 30 criteria.

They wanted to reduce the concentration of nitrogen to below 10 milligrams per liter, the cost to below $20,000 to install and the lifespan of the system to 30 years.

The center developed nitrogen removing biofilters, or NRBs.

In a second paper, the researchers showed that the NRBs removed 80 to 90 percent of nitrogen.

At the same time, the NRBs are removing nearly 60 percent of 1,4 dioxane, driving the concentration down to levels that are at, or below, the concentration in tap water, which is 1 part per billion.

This is the “first published study to demonstrate a significant removal of 1,4 dioxane,” Gobler said at the press conference. NRBs have advanced “to the piloting stage.”

The center anticipates that the NRBs could be available for widespread installation throughout Suffolk County by June 2022.

The center currently has 20 NRBs in the ground and will have over 25 by the end of the year. In 2022, anyone should be able to install them, Gobler said.

Residents interested in NRBs can contact the center, which is “working toward being prepared for widespread installation,” Gobler explained in an email.

Residents interested in learning what financial assistance they might receive for a septic improvement program can find information at the website www.reclaimourwater.info.

Gobler said the microbes in the NRBs do the work of removing nitrogen and 1,4 dioxane, which continually reside within the filters. He explained that they should continue to be functional for decades.

Adrienne Esposito, executive director of Citizens Campaign for the Environment, which has offices in five locations and is committed to an environmental agenda, was pleased with the research Gobler and Venkatesan presented.

She was “beyond thrilled with the science released today,” she said during the press conference. This research on the effectiveness of the NRBs “validates all of the work going on for the last four years.”

Esposito urged the state’s Department of Environmental Conservation to test wastewater from laundromats, car washes and other sources to determine the amount of 1,4 dioxane that enters into groundwater and surface water systems.

Esposito is “thankful for science-based work that allows us to attain clean water.”