By Patricia Paladines

West Meadow Beach is one of four locations in New York State where horseshoe crabs are protected from capture for the biomedical and bait fishing industries throughout the year. It is a beach where during full moons of May and June we can witness an annual event that has been occurring for thousands of years in this part of the world; the migration of horseshoe crabs from the depths of the Long Island Sound to mate and deposit eggs on the shore at high tide. The beach’s sand bars are literally where single males and females “hook-up.”

Horseshoe crabs (Limulus polyphemus) have roamed the seas for over 400 million years. Long Island’s north shore, having existed for just around 20,000 years, is a relatively new site for the romantic rendezvous.

I’ve led walks for the Four Harbors Audubon Society at West Meadow Beach where we’ve counted hundreds of horseshoe crabs on the stretch of beach between the parking lot and the jetty on the southern end. On a recent solo walk, I came upon a fisherman who had reeled in a horseshoe crab. He was about to use a knife to tear the baited hook out of the horseshoe crab’s mouth. I stopped him and showed him how easy it was to remove the hook by hand. He said he had been told the crabs were dangerous and that the tail could hurt you. After informing him that was incorrect, I took the crab and placed it back in the water while letting him know these animals are protected on this beach.

I may have come upon the scene just in time to save that horseshoe crab, but the beach was littered with the shells of other crabs that appeared to have been purposely killed. On the same walk I found a large female who had been smashed by a piercing object. A few weeks ago, a couple of friends found a horseshoe crab that appeared to have been burned. There is evidence of many overnight bonfires on the dunes, some very near the piping plover nest barricades.

Dead horseshoe crabs were not the only bottom feeding sea creatures strewn along the beach. Sun dried sea robins and a few skates also littered the high tide line.

It was late afternoon and the beach was filling up with fisher folks, both men and women. That meant there would be a lot of bait attracting bottom feeding animals, AKA scavengers, fish and crabs that stroll the sea floor feeding on whatever they can find. Fisherman’s bait is easy pickings, but not the safest, especially if you are not a species preferred on that fisherman’s plate.

I spotted two fishermen who had just reeled in two sea robins. I went over to ask them what they were going to do with them. They told me they were going to throw them back, but then I noticed a live sea robin on the sand just behind them. I picked it up and threw it back in the water hoping they would do the same with the ones they had on their hooks. I continued my walk near the line of fisher people and found more live sea robins on the sand and threw them all back in the Sound. One woman told me the fish just wash up on the beach with the waves. No, that doesn’t happen.

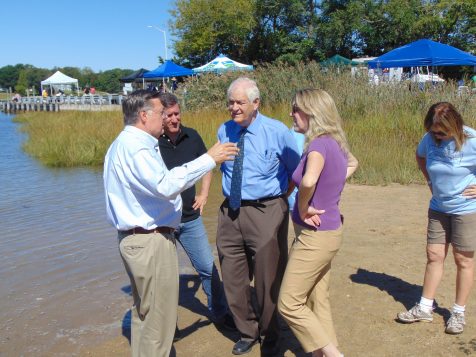

I came out for a walk to find peace in the natural beauty this beach offers Brookhaven residents; instead, what I found was upsetting. I talked to a few of the fishermen and learned that some are coming from Nassau County and Queens. Do these people have permits to fish on Brookhaven Town beaches?

When granted a fishing permit, does the person receive educational material about our local sea creatures and respectful beach use etiquette? The beach is littered not only with dead animals, but also fishing-related garbage — hooks, lines, plastic bags advertising tackle. Educational material should be in various languages. I’m a native Spanish speaker so was able to speak to the Spanish and English-speaking fisher people in the language they were most comfortable with. My experience as an environmental educator on Long Island has informed me that there are speakers of many languages who enjoy catching their meals from our waters; Czech, Polish, and Chinese are some of the other languages I’m aware of.

Education and patrolling are needed on our beaches. Additionally, West Meadow Beach should be closed to fishing during the horseshoe crab breeding season; allowing fishing during this time is counterproductive to efforts in place to protect a species whose numbers continue to decline along the Atlantic Coast.

Patricia Paladines is an Adjunct Instructor at Stony Brook University’s School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences and Co-President of Four Harbors Audubon Society.