By Daniel Dunaief

Growing up in Hooper, a small town in the central part of Nebraska, Jon Heusel considered following in his parents’ footsteps.

His father William took him on house calls where he provided for a wide range of medical needs.

Along the way, however, Heusel, whose mother Mona was also an intensive care unit nurse towards the end of her career, discovered genetics and immunology as he earned his bachelor’s degree at the University of Nebraska and then his MD, PhD at the University of Washington in St. Louis.

Enamored with these sciences and inspired to pursue a path of patient care from a different perspective, Heusel blazed his own trail, albeit one in which health care remained a professional focus.

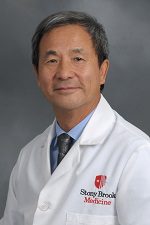

Indeed, the second-generation doctor, who became Vice Chair for Clinical Pathology at the Renaissance School of Medicine at Stony Brook University on October 2nd, has devoted his career to the translation of new technologies into healthcare solutions.

For the past decade, this involved next generation sequencing, but also other new technologies and computerized systems for analyzing the data.

Heusel is inspired by a drive to improve the healthcare at academic medical centers like Stony Brook and Washington University, where new discoveries can affect positive change.

“The more I learned about Stony Brook, which is an up-and-coming university, the more I thought it was a magnificent opportunity for me,” said Heusel, who admired the recent jump Stony Brook University has made in the U.S. News and World Report rankings.

Mandate

Pathology Chair Kenneth Shroyer described Heusel as a “wonderful recruitment” and believes his background makes him especially well suited to his role.

“We want to develop in-house capacity to do advanced molecular testing to find actionable mutations that could inform therapeutic decision making,” said Shroyer. “He’s extremely experienced in that area.”

Shroyer suggested Stony Brook wants to develop opportunities for advanced sequencing technology within the molecular pathology lab, with a focus on molecular oncology.

Heusel described the development of a comprehensive diagnostic service in cancer as a high priority.

The cost of building new services with new technologies will require significant investment. The Pathology Department will work in partnership with the Cancer Center to build services.

“Ideally, the clinical services we build will also be attractive in supporting research and contract testing from companies in the pharmaceutical and biotech spaces,” Heusel explained.

By using informatics and digital pathology, Stony Brook can become a place where medical students and professionals in related areas including computational biology, genetic counseling and oncology increasingly want to come.

Heusel particularly appreciates the opportunity to translate technology and science into healthcare solutions.

“If you do this correctly, the tests, systems, programs and people you have recruited to run them will extend far into the future,” he said. “When this happens, you leave behind a legacy of excellence.”

Heusel will replace Eric Spitzer, who will retain his role of medical director of labs until Heusel takes over that role in January.

Shroyer described Spitzer’s contributions to the department and hospital as “tremendous,” adding that he has “been outstanding in his position as leader of the hospital laboratory. While we know [Heusel] is going to be extremely successful in part due to [Spitzer’s] help in the transition phase, we’re still going to miss” Spitzer.

Spitzer has been a valuable counselor to Shroyer and a mentor to many and is an “outstanding educator” who has been a “very impactful educator for our residents and medical students,” Shroyer said.

Educational opportunities

Heusel not only has ambitions for the university, but also for himself in his new job.

The new pathology vice chair is looking for opportunities to put his knowledge and instincts to work to make Stony Brook better — even if only in the slightest of ways, he said.

“The tumblers of fate must align themselves to become opportunities for transformational leadership; those are relatively rare,” he explained. “It’s my hope that I am well prepared and can recognize them when they cross my path.”

As for the public, Heusel recognizes that primary school teachers have a tough job in educating the public in general and in sharing the intricacies of science such as genetics. He admires them for their work.

He suggested that primary education could be reimagined amid the exponential growth in knowledge.

“I am hopeful that biology and genetics will be taught in a way that empowers people to understand their bodies and their health or disease better, but I think it is more important to teach our children to think critically,” he explained.

Part of Heusel’s job is to make the results of complex testing accessible to patients and, in many cases, their doctors.

“The growing importance of genetics in our understanding of health and disease means people will, over time, gain new insights simply because they are reading and hearing about these concepts much more often,” he explained. “It also highlights the critical role that well trained genetic counselors have in the healthcare of today and the foreseeable future.”

Heusel and his wife Jean enjoy living in the Stony Brook area, where they have found the people welcoming. In the past, they have gone scuba diving and sky diving and have also done canoeing, hiking, kayaking and skiing.

As they have gotten older, they have tended towards quieter experiences. They have found the West Meadow Beach sunsets “amazing” and have enjoyed their introduction to shows at the Staller Center for the Arts.

Heusel also appreciates a life outside work that includes working with wood, painting, doing pottery, cooking and making up poems, songs on the ukulele and bad puns.

His parents generated a sense of compassion in Heusel and his sisters, with a “wonder of the human body, and with the ability to find humor in almost anything.”

As for his work, Heusel is thrilled that Shroyer recruited him to join the university. He admits, though, that he has had to adjust to local driving styles.

“I am surprised by the aggressive manner in which people drive inside their cars which is so very opposite from the friendliness they exude outside of them,” he said.