Reviewed by Jeffrey Sanzel

Zach Braff is best known for his acting work, most notably for his nine seasons as Dr. J.D. Dorian on the sitcom Scrubs. Additionally, his extensive work behind the camera includes producing, writing, and directing. The works encompass short films, television, and, most notably, the feature film Garden State (2004), a quirky but effective rom-com featuring Braff and Natalie Portman. Unfortunately, his follow-up, the domestic comedy-drama Wish I Was Here (2014), was not well-received.

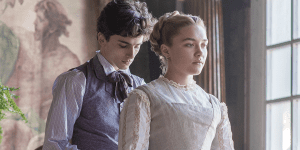

Braff’s third offering, A Good Person, is a drama of dysfunction and addiction. The film opens with Morgan Freeman’s voiceover as he works on his model trains, wistfully proffering the idea that life is neither neat nor tidy. Then, the idyllic moment shifts to the raucous engagement party of Allison (Florence Pugh) and Nathan (Chinaza Uche). Allison sings an original song to her future husband, much to the delight of the guests.

The next morning, Allison drives her future sister-in-law and brother-in-law from New Jersey into New York City. Checking the map app on her phone, Allison involves them in an accident where her prospective in-laws die.

A year later, Florence is an unemployed pharmaceutical rep addicted to pills. She lives in a perpetual state of conflict with her mother, Diane (Molly Shannon), who lacks the insight or emotional resources to help her struggling daughter. Florence has run through her oxy, and none of her doctors will refill her prescription. After a failed attempt to blackmail a former colleague, she ends up in a bar where she smokes with two low-lifes with whom she had gone to high school. Florence has hit bottom.

She attends an AA meeting, running into Daniel (Morgan Freeman), the man who would have been her father-in-law. She leaves, but Daniel stops her, suggesting fate has brought them together. They form an odd bond that becomes a tenuous friendship.

Retired Daniel was a cop for forty years and a drunk for fifty. Sober ten years, he grapples with raising his orphaned granddaughter, the now rebellious Ryan (Celeste O’Connor). He accepts that he does not know how to raise a teenager, having left that to his wife. The worlds collide as Allison and Ryan accidentally meet at Daniel’s house and also form a strained connection. Ryan shares her late mother’s feelings that Allison was the best thing to happen to her uncle Nathan. Ryan lets slip that her grandfather blames Allison for the accident.

The film is rife with revelations and the sharing of histories. An alcoholic father abused Daniel. In turn, Daniel became a blackout drunk, mistreating his own children. In an inebriated rage, Daniel beat Nathan so severely that the boy lost hearing in his right ear. Estranged, the adult Nathan and Daniel have only the slightest of relationships.

While the film covers no new territory, the narrative contains the makings of a dramatic and interesting story. Sadly, the gap between intention and execution can be the distance between Perth Amboy and Perth, Australia.

The film tackles difficult subject matters—guilt, addiction, withdrawal, forgiveness—but somehow manages to avoid depth. Director Braff works from his screenplay, which seems a patchwork of acting class scenes. The occasional smart quip—“the opiate of the masses is opium”—is lost among aphorisms and cliches—“Comparison is the thief of joy.”

Daniel’s Viet Nam veteran cap is jaw-droppingly unsubtle. In a film brimming with life and death issues, the result is often tensionless and pedestrian. The metaphors—the model trains, Allison’s father’s watch, swimming, songwriting—even a haircut—are heavy-handed.

However, while Braff the writer might have failed, he cast well and brought out strong performances. Florence Pugh finds the anguish and ugliness in Allison’s spiral. She is mesmerizing rawness in every moment, alternating between a hyper-aware ferocity and a disconnected stupor. Morgan Freeman is incapable of shoddy work and remains one of the most watchable cross-genre actors. While Daniel sits in the center of his range, he manages to nuance the darker moments, contrasted with Freeman’s often-seen “wise” humor.

Molly Shannon’s mother is a bit shrill, but her brittleness and immaturity are not misplaced. Chinaza Uche is given little more than shades of pain, but what he does is imbued with sincerity. Twenty-something Celeste O’Connor embodies the angry teenager, Ryan, and easily holds her own against Pugh and Freeman. She proffers fire, grief, and even joy, while hovering on the verge of implosion.

So much of A Good Person feels manipulated, if not downright manipulative. Ultimately, Braff confuses messy lives with sloppy filmmaking.

Rated R, the film is now playing in local theaters.