By Daniel Dunaief

Some day in the not too distant future, an astronaut may approach rocks on the moon and, with a handheld instrument, determine within minutes whether the rock might have value as a natural resource or as a source of historical information.

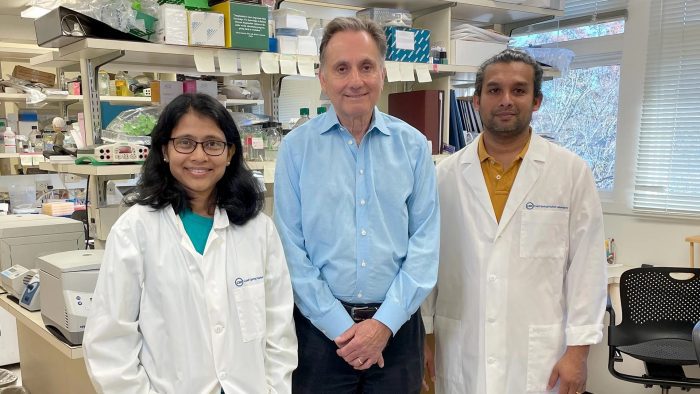

That’s the vision Nandita Kumari, a fourth-year graduate student in the Department of Geosciences in the College of Arts and Sciences at Stony Brook University, has.

In the meantime, Kumari was part of a multi-institutional team that recommended two landing sites in the moon’s south polar region for future Artemis missions.

The group, which included students from the University of Arizona, the University of California Los Angeles, and the University of Buffalo, used several criteria to recommend these two sites.

They looked at the resources that might be available, such as water and rocks, at how long the areas are in sunlight and at how the features of the land, from the slope of hills to the size of boulders, affects the sites accessibility.

“These two sites ended up fulfilling all these criteria,” Kumari said. Models suggest water might be present and the regions are in sunlight more than 80 percent of the time, which is critical for solar-powered devices.

The group used high-resolution data from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter to create a map of all the rocks and to model the geological diversity of the site. They used infrared images to gather data from areas when they were dark. They also added temperature readings.

To the delight of the team, NASA selected both of the sites as part of a total of 13 potential landing locations.

Planetary scientist David Kring advised the group during the process. Kring has trained astronauts and worked on samples brought back from the Apollo missions.

At the end of the first year of her PhD, Kumari received encouragement to apply for the virtual internship with Kring from Stony Brook Geosciences Professor Tim Glotch, who runs the lab where she has conducted her PhD work.

Putting a number on it

Kumari said her thesis is about using machine learning to understand the composition of resources on the moon. She would like to use artificial intelligence to delve deeply into the wealth of data moon missions and observations have been collecting to use local geology as a future resource.

“Instead of saying something has a ‘little’ or a ‘lot’” of a particular type of rock that might have specific properties, she would like to put a specific numerical value on it.

An engineer by training, Kumari said she is a “very big fan of crunching numbers.”

Since joining the lab, Kumari has become “our go-to source for any type of statistical analysis me or one of my other students might want to conduct,” Glotch explained.

The work Kumari has done provides “large improvements over traditional spectroscopic analysis techniques,” Glotch added.

In examining rocks for silicic properties, meaning those that contain silicon, most scientists describe a rock as being less or more silicic, Kumari said.

“It’s difficult to know whether 60 percent is high or 90 percent is high,” she added. Such a range can make an important difference, and provides information about history, formation and thermal state of the planet and about potential resources.

With machine learning that trains on data collected in the lab, the model is deployed on orbiter data.

The machine learning doesn’t stop with silica. It can also be extended to search for helium 3 and other atoms.

Understanding and using the available natural resources reduces the need to send similar raw materials to the moon from Earth.

“There has to be a point where we stop” transporting materials to the moon, said Kumari. “It’s high time we use modern practices and methods so we can go through really large chunks of data with limited error.”

The machine learning starts with a set of inputs and outputs, along with an algorithm to explain the connection. As it sorts through data, it compares the outputs against what it expects. When the data doesn’t match the algorithm, it adjusts the algorithm and compares that to additional data, refining and improving the model’s accuracy.

A love for puzzles

Kumari, who grew up in Biharsharif, India, a small town in the northern state of Bihar, said this work appeals to her because she “loves puzzles that are difficult to solve.” She also tries to find solutions in the “fastest way possible.”

Kumari was recently part of a field exploration team in Utah that was processing data. The team brought back data and manually compared the measurements to the library to see what rocks they had.

She wrote an algorithm that provided the top five matches to the spectroscopic measurements the researchers found. Her work suggested the presence of minerals the field team didn’t anticipate. What’s more, the machine provided the analysis in five minutes.

The same kind of analysis can be used on site to study lunar rocks.

“When astronauts go to the moon, we shouldn’t require geology experts to be there to find the best rocks” she said. While having a geologist is the best-case scenario, that is not always possible. “Anyone with a code in their instruments should be able to decide whether it is what they’re looking for.”

As for her interest in space travel, Kumari isn’t interested in trekking to the moon or Mars.

While she believes the moon and Mars should be a base for scientific experiments, she doesn’t think people should focus on colonizing either place.

Such colonization ideas may reduce the importance of working on the challenges humans have created on Earth, including climate change.

“You can’t move to Mars,” Kumari said. The litmus test for that occurred during Covid, when people had to isolate.

“If we couldn’t stay in our homes with all the comfort and everything, I do not see a future where this would be possible with stringent constraints on Mars,” she added.

An advocate for women in STEM fields, Kumari said women should pursue scientific careers even if someone else focuses on their mistakes or tries to break their confidence.

“The only way to stop this from happening is to have women in higher places,” she explained. “We should also be supportive of each other and grow together.”