By Daniel Dunaief

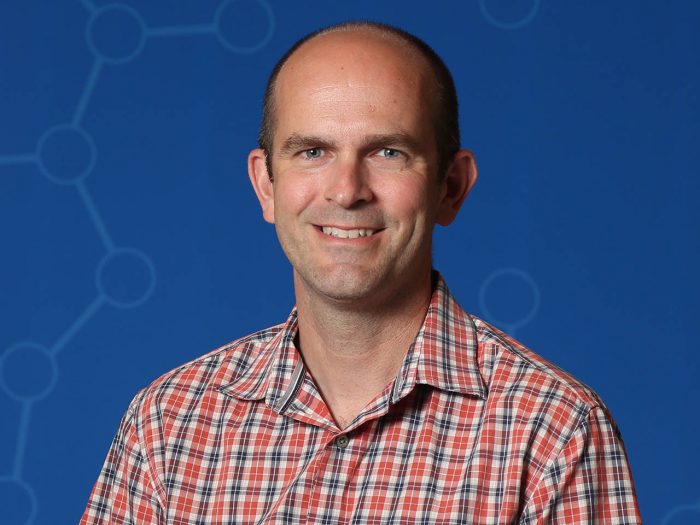

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Professor Mikala Egeblad thought she saw something familiar at the beginning of the pandemic.

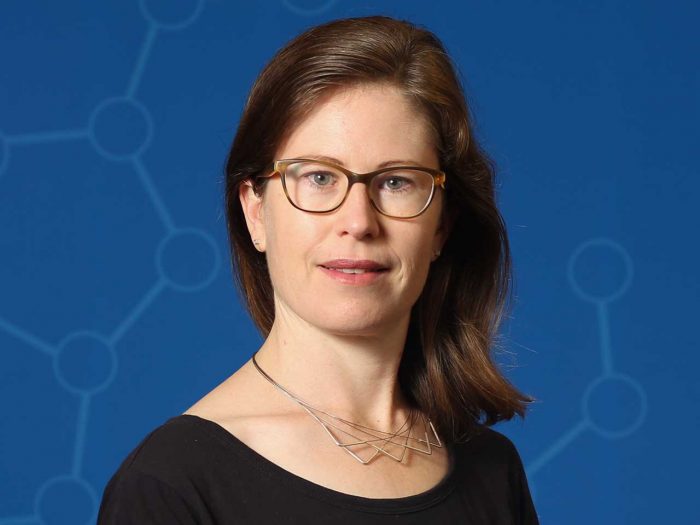

Egeblad has focused on the way the immune system’s defenses can exacerbate cancer and other diseases. Specifically, she studies the way a type of white blood cell produces an abundance of neutrophil extracellular traps or NETs that can break down diseased and healthy cells indiscriminately. She thought potentially high concentrations of these NETs could have been playing a role in the worst cases of COVID.

“We got the idea that NETs were involved in COVID-19 from the early reports from China and Italy” that described how the sickest patients had severe lung damage, clotting events and damage to their kidneys, which was what she’d expect from overactive NETs, Egeblad explained in an email.

Recently, she, her post doctoral researcher Jose M. Adrover and collaborators at Weill Cornell Medical College and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mt. Sinai proved that this hypothesis had merit. They showed in hamsters infected with COVID and in mice with acute lung injuries that disabling these NETs improved the health of these rodents, which strongly suggested that NETs are playing a role in COVID-19.

“It was very exciting to go from forming a hypothesis to showing it was correct in the context of a complete new disease and within a relatively short time period,” Egeblad wrote.

Egeblad, Andover and their collaborators recently published their work in the Journal of Clinical Investigation Insight.

Importantly, reducing the NETs did not alter how much virus was in the lungs of the hamsters, which suggests that reducing NETs didn’t weaken the immune system’s response to the virus.

Additional experiments would be necessary to prove this is true for people battling the worst symptoms of COVID-19, Egeblad added.

While the research is in the early stages, it advances the understanding of the importance of NETs and offers a potential approach to treating COVID-19.

An unexpected direction

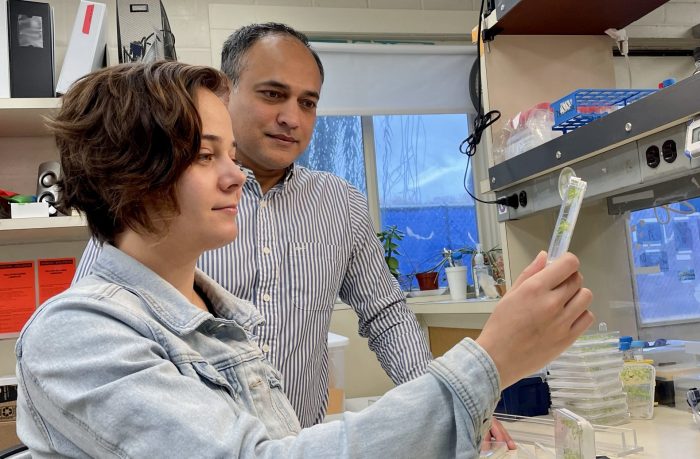

When Adrover arrived from Spain, where he had earned his PhD from the Universidad Complutense de Madrid and had conducted research as a post doctoral fellow at the Spanish Center for Cardiovascular Research in March of 2020, he expected to do immune-related cancer research.

Within weeks, however, the world changed. Like other researchers at CSHL and around the world, Egeblad and Adrover redirected their efforts towards combating COVID.

Egeblad and Andover “were thinking about the virus and what was going on and we thought about trying to do something,” Adrover said.

Egeblad and Adrover weren’t trying to fight the virus but rather the danger from overactive NETs in the immune system.

Finding an approved drug

Even though they were searching for a way to calm an immune system responding to a new threat, Egeblad and Adrover hoped to find a drug that was already approved.

After all, the process of developing a drug, testing its safety, and getting Food and Drug Administration approval is costly and time-consuming.

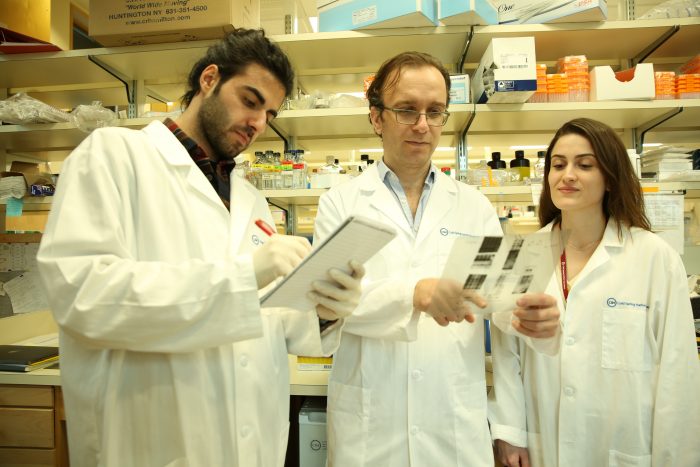

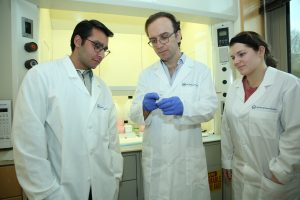

That’s where Juliane Daßler-Plenker, also a postdoctoral fellow in Egeblad’s lab, came in. Daßler-Plenker conducted a literature search and found disulfiram, a drug approved in the 1950’s to treat alcohol use disorder. Specifically, she found a preprint reporting that disulfuram can target a key molecule in macrophages, which are another immune cell. Since the researchers knew this was important for the formation of NETs, Daßler-Plenker proposed that the lab test it.

Working with Weill Cornell Medical College and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mt. Sinai, Adrover explored the effect of disulfiram, among several other possible treatments, on NET production.

Using purified neutrophils from mice and from humans, Adrover discovered that disulfiram was the most effective treatment to block the formation of NETs.

He, Assistant Professor Robert Schwartz’s staff at Weill Cornell and Professor Benjamin tenOever at Mt. Sinai tried disulfiram on hamsters infected with SARS-Cov-2. The drug blocked net production and reduced lung injury.

The two experiments were “useful in my opinion as it strengthens our results, since we blocked NETs and injury in two independent models, one of infection and the other of sterile injury,” Adrover said. “Disulfuram worked in both models.”

More work needed

While encouraged by the results, Egeblad cautioned that this work started before the availability of vaccines. The lab is currently investigating how neutrophils in vaccinated people respond to COVID-19.

Still, this research offered potential promise for additional work on NETs with some COVID patients and with people whose battles with other diseases could involve some of the same immune-triggered damage.

“Beyond COVID, we are thinking about whether it would be possible to use disulfiram for acute respiratory distress syndrome,” Egeblad said. She thinks the research community has focused more attention on NETs.

“A lot more clinicians are aware of NETs and NETs’ role in diseases, COVID-19 and beyond,” she said. Researchers have developed an “appreciation that they are an important part of the immune response and inflammatory response.”

While researchers currently have methods to test the concentration of NETs in the blood, these tests are not standardized yet for routine clinical use. Egeblad is “sensing that there is more interest in figuring out how and when to target NETs” among companies hoping to discover treatments for COVID and other diseases.

The CSHL researcher said the initial race to gather information has proven that NETs are a potentially important target. Down the road, additional research will address a wide range of questions, including what causes some patients to develop different levels of NETs in response to infections.