By Tara Mae

Saltwater and sea air can replenish, rather than rust the spirit. Any means of water conveyance is a line to liveliness and livelihood, a rope that links us to the generations that came before. Set sail into Long Island’s local maritime past with Small Wooden Boats: The Forgotten Workhorses and Leisure Craft of Old at the Port Jefferson Village Center, on view now through October.

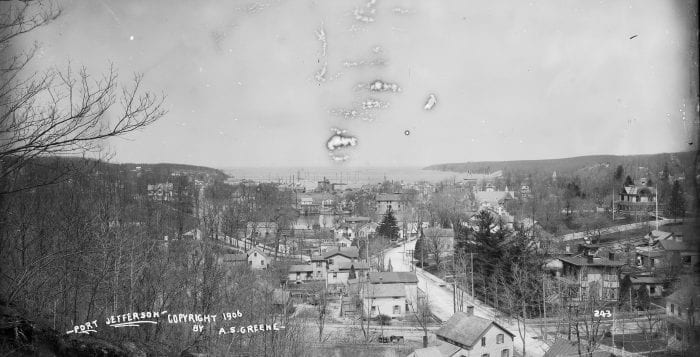

Located on the second floor of the building, with a topical view of the harbor, the photo exhibit features approximately 60 photographs, mainly ranging 24-36 inches. Through the lens of wooden boats, it explores the labor and leisure of primarily 19th and early 20th century islanders and vacationers.

“There are two distinct categories of images. People using small boats to fish, clam, transport items, and people enjoying the summer in the bathing fashion of the period,” Port Jefferson Village Historian Christopher Ryon, who curated the exhibit, said.

Skimmed from the village’s own archive, first compiled by previous historian Ken Brady, the catalog has amassed tens of thousands of photographs. Its selection includes access to pictures that other organizations, like Three Village Historical Society, possess. The breadth and depth of data highlights the profound impact of beach culture on this area.

Small Wooden Boats is a tribute to and testimonial the scope of people’s sometimes shifting, yet still steadfast, relationship to the sea.

“The photos in this show capture the serene atmosphere of small boats and people on the shoreline of harbors and ponds. From clammers and fishermen to women in dresses, you can imagine the feel of the water on their feet and the sound of the water as they walk,” explained Ryon during a tour of the exhibit.

In locations familiar to residents, such as West Meadow Beach, Pirates Cove and Port Jefferson Harbor, their predecessors pose in the Long Island Sound and from shore.

Penn No. 1, a small tugboat that maneuvered goods and equipment for Suffolk Dredging Corporation, seems at a standstill as two presumed employees appear portside. One man, still wearing his work gloves, leans jauntily against an unidentifiable object.

A little girl in a swim costume, somewhat faded with age, grins at the camera as she wades water with a flotation device tied around her waist.

Men, women, and children, wearing street clothes, sit in floating repose aboard rowboats as three other male figures, perhaps lifeguards, stand behind them, staring purposefully into the distance. An empty dinghy is tied up to their right as waves break against the mooring.

Individuals who appear as salt of the earth or buoyantly effervescent, all of these figures are both anchored to their era and adrift on the sea of time. Though their attire and apparel are different, they share a relationship with the water that is more familiar than foreign.

“This exhibit exemplifies Port Jefferson’s history as a shipbuilding port, a transportation hub, a fishing, clamming, oystering community, and, of course, a tourist destination,” Ryon said

Essential elements of this dualistic dynamic have evolved or become endangered but their essence remains accessible to those who seek to acknowledge, even enjoy, the ebb and flow of people’s dependence on the surrounding water.

By design, the show displays the dichotomies of work and play. Pictures in Small Wooden Boats are harbingers of changing tides, before nautical industry was overtaken by seaside recreation.

Such developments are embodied by the Village Center itself, which has its own ties to maritime history. Situated on the grounds of the Bayles Shipyard, the building originally housed a machine shop and mould loft, established in 1917 during World War I.

That same year, the Bayles family sold it. After changing hands, it was acquired by the New York Harbor Dry Dock Corporation, which in 1920, closed the shipyard, and fired all of its workers except for a skeleton crew. Following different business iterations, the Village Center was founded there in 2005.

The enmeshment of past and present also underscores how the Sound remains intertwined in life on land, a message that Ryon seeks to bring to the masses through ongoing nautical projects.

Besides the exhibit, another such endeavor is the construction of a replica whaleboat, dubbed Caleb Brewster, a seafaring vessel that will ideally launch in 2024.

Named in honor of the Culper Spy Ring member who ran messages via his whaleboat between Long Island, under British occupation, and Connecticut, where General George Washington was stationed, it is a community undertaking. A crew of volunteers, among them students from an Avalon Nature Preserve program, is helping construct and assemble the whaleboat. And, in part as an homage to the village center’s heritage, it is being built in the Bayles Boat Shop located just a stone’s throw from the Village Center across from Harborfront Park.

Construction of the Caleb Brewster and the Small Wooden Boats exhibit are part of a continuous effort to bring more attention to the common, simple sea craft that are so integral to the existence and entertainment an island provides.

“The bigger boats, like schooners tend to get more notice, while the smaller ones are doing hard work moving materials and people,” Ryon said. “We [the village center] have this huge collection of stuff. We have done lots of different types of shows here, and small boats are part of the collection that I now want to showcase. I look forward to seeing people enjoying the exhibit.”

The community is invited to an opening reception to Small Wooden Boats: The Forgotten Workhorses and Leisure Craft of Old on Sunday, Sept. 10 from 2 to 3:30 p.m. on the second floor of the Port Jefferson Village Center, 101 East Broadway, Port Jefferson. Viewing hours for the exhibit are 9 a.m. to 8 p.m. daily through Oct. 31. For more information, call 631-473-4778.

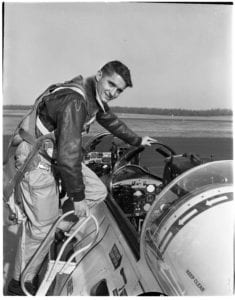

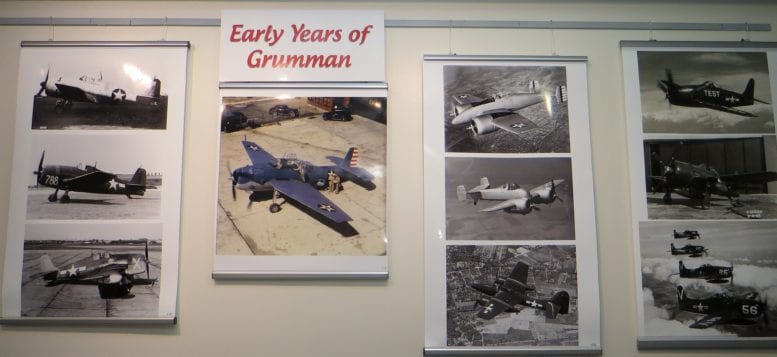

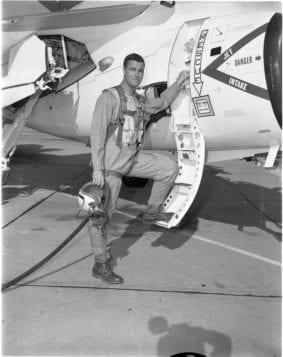

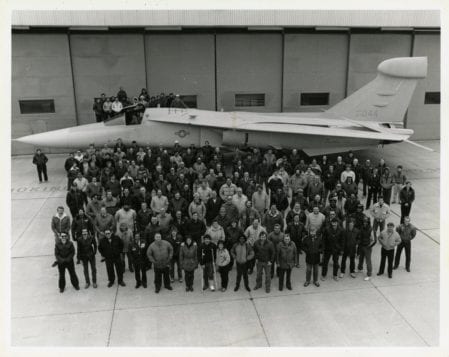

Kicking off tonight with a discussion and reception, the Port Jefferson Village Center will present an exhibit titled Grumman on Long Island, A Photographic Tribute featuring photographs and memorabilia from Grumman. The company, which became part of Northrop Grumman in 1994, started in 1929 and was involved in everything from the design of F-14 fighter jets to the lunar excursion module that carried astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin to the surface of the moon 50 years ago this July.

Kicking off tonight with a discussion and reception, the Port Jefferson Village Center will present an exhibit titled Grumman on Long Island, A Photographic Tribute featuring photographs and memorabilia from Grumman. The company, which became part of Northrop Grumman in 1994, started in 1929 and was involved in everything from the design of F-14 fighter jets to the lunar excursion module that carried astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin to the surface of the moon 50 years ago this July.