Medical Compass: Parkinson’s Disease – reducing risk and slowing progression

Recent research focuses on modest lifestyle changes

By David Dunaief, M.D.

Parkinson’s disease has burst into the public consciousness in recent years. It is a neurodegenerative (the breakdown of brain neurons) disease with the resultant effect of a movement disorder.

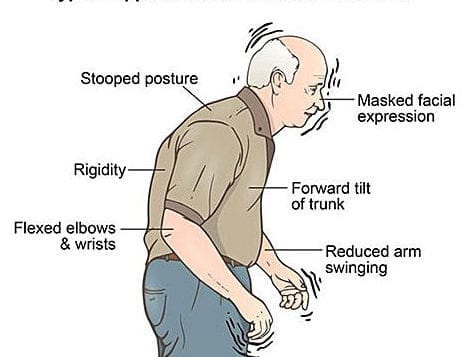

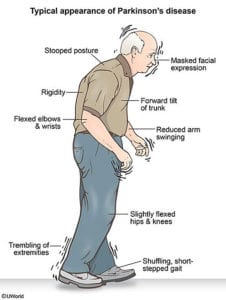

Most notably, patients with the disease suffer from a collection of symptoms known by the mnemonic TRAP: tremors while resting, rigidity, akinesia/bradykinesia (inability/difficulty to move or slow movements) and postural instability or balance issues. It can also result in a masked face, one that has become expressionless, and potentially dementia, depending on the subtype. There are several different subtypes; the diffuse/malignant phenotype has the highest propensity toward cognitive decline (1).

The part of the brain most affected is the basal ganglia, and the prime culprit is dopamine deficiency that occurs in this brain region (2). Why not add back dopamine? Actually, this is the mainstay of medical treatment, but eventually the neurons themselves break down, and the medication becomes less effective.

Risk factors may include head trauma, reduced vitamin D, milk intake, well water, being overweight, high levels of dietary iron and migraine with aura in middle age.

Is there hope? Yes, in the form of medications and deep brain stimulatory surgery, but also with lifestyle modifications. Lifestyle factors include iron, vitamin D and CoQ10. The research, unfortunately, is not conclusive, though it is intriguing.

Let’s look at the research.

The role of iron

This heavy metal is potentially harmful for neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, macular degeneration, multiple sclerosis and, yes, Parkinson’s disease. The problem is that this heavy metal can cause oxidative damage.

In a small, yet well-designed, randomized controlled trial (RCT), researchers used a chelator to remove iron from the substantia nigra, a specific part of the brain where iron breakdown may be dysfunctional. An iron chelator is a drug that removes the iron. Here, deferiprone (DFP) was used at a modest dose of 30 mg/kg/d (3). This drug was mostly well tolerated.

The chelator reduced the risk of disease progression significantly on the Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS).

Participants who were treated sooner had lower levels of iron compared to a group that used the chelator six months later. A specialized MRI was used to measure levels of iron in the brain. This trial was 12 months in duration.

The iron chelator does not affect, nor should it affect, systemic levels of iron, only those in the brain specifically focused on the substantia nigra region. The chelator may work by preventing degradation of the dopamine-containing neurons. It also may be recommended to consume foods that contain less iron.

CoQ10

When we typically think of using CoQ10, a coenzyme found in over-the-counter supplements, it is to compensate for depletion from statin drugs or due to heart failure. Doses range from 100 to 300 mg. However, there is evidence that CoQ10 may be beneficial in Parkinson’s at much higher doses.

When we typically think of using CoQ10, a coenzyme found in over-the-counter supplements, it is to compensate for depletion from statin drugs or due to heart failure. Doses range from 100 to 300 mg. However, there is evidence that CoQ10 may be beneficial in Parkinson’s at much higher doses.

In an RCT, results showed that those given 1,200 mg of CoQ10 daily reduced the progression of the disease significantly based on UPDRS changes, compared to the placebo group (4). Other doses of 300 and 600 mg showed trends toward benefit but were not significant. This was a 16-month trial in a small population of 80 patients. Though the results for other CoQ10 studies have been mixed, these results are encouraging. Plus, CoQ10 was well tolerated at even the highest dose. Thus, there may be no downside to trying CoQ10 in those with Parkinson’s disease.

Vitamin D: Good or bad?

In a prospective (forward-looking) study, results show that vitamin D levels measured in the highest quartile reduced the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease by 65 percent, compared to the lowest quartile (5). This is quite impressive, especially since the highest quartile patients had vitamin D levels that were what we would qualify as insufficient, with blood levels of 20 ng/ml, while those in the lowest quartile had deficient blood levels of 10 ng/ml or less. There were over 3,000 patients involved in this study with an age range of 50 to 79.

When we think of vitamin D, we wonder whether it is the chicken or the egg. Let me explain. Many times we are deficient in vitamin D and have a disease, but replacing the vitamin does nothing to help the disease. Well, in this case it does. It turns out that vitamin D may play dual roles of both reducing the risk of Parkinson’s disease and slowing its progression.

In an RCT, results showed that 1,200 IU of vitamin D taken daily may have reduced the progression of Parkinson’s disease significantly on the UPDRS compared to a placebo over a 12-month duration (6). Also, this amount of vitamin D increased the blood levels by two times from 22.5 to 41.7 ng/ml. There were 121 patients involved in this study with a mean age of 72.

So, what have we learned? Though medication with dopamine agonists is the gold standard for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease, lifestyle modifications can have a significant impact on both prevention and treatment of this disease. Each lifestyle change in isolation may have modest effects, but cumulatively they might pack quite a wallop. The most exciting part is that lifestyle modifications have the potential to slow the progression of the disease and thus have a protective effect. Iron chelators specific to the brain may also be very important in disease modification. This also brings vitamin D back into the fold as a potential disease modifier.

References:

(1) JAMA Neurol. 2015;72:863-873. (2) uptodate.com. (3) Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;10;21(2):195-210. (4) Arch Neurol. 2002;59(10):1541-1550. (5) Arch Neurol. 2010;67(7):808-811. (6) Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97(5):1004-1013.

Dr. Dunaief is a speaker, author and local lifestyle medicine physician focusing on the integration of medicine, nutrition, fitness and stress management. For further information, visit www.medicalcompassmd.com or consult your personal physician.