By Daniel Dunaief

Rain, rain go away, come again some other day.

The days of wishing rain away have long since passed, amid the reality of a wetter world, particularly during hurricanes in the North Atlantic.

In a recent study published in the journal Nature Communications, Kevin Reed, Associate Professor and Associate Dean of Research at the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences at Stony Brook University, compared how wet the hurricanes that tore through the North Atlantic in 2020 would have been prior to the Industrial Revolution and global warming.

Reed determined that these storms had 10 percent more rain than they would have if they occurred in 1850, before the release of fossil fuels and greenhouse gases that have increased the average temperature on the planet by one degree Celsius.

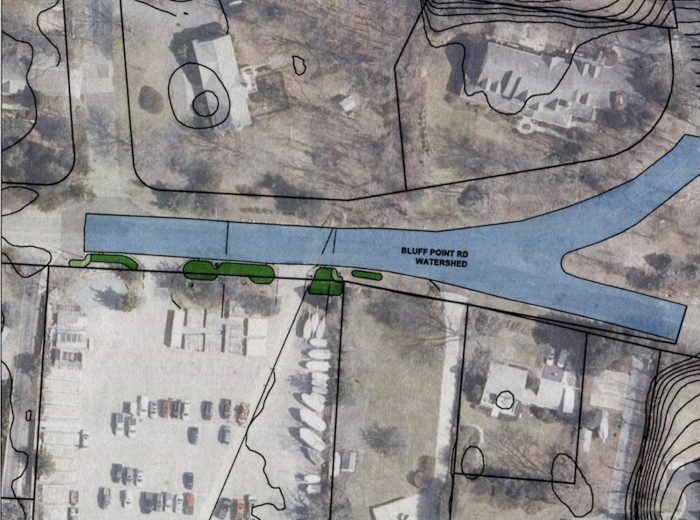

The study is a “wake up call to the fact that hurricane seasons have changed and will continue to change,” said Reed. More warming means more rainfall. That, he added, is important when planners consider making improvements to infrastructure and providing natural barriers to flooding.

While 10 percent may not seem like an enormous amount of rain on a day of light drizzle and small puddles, it represents significant rain amid torrential downpours. That much additional rain can be half an inch or more of rain, said Reed. Much of the year, Long Island may not get half an inch a day, on top of an already extreme event, he added.

“It could be the difference between certain infrastructure failing, a basement flooding” and other water-generated problems, he said. The range of increased rain during hurricanes in 2020 due to global warming were as low as 5 percent and as high as 15 percent.

While policy makers have been urging countries to reach the Paris Climate Accord’s goal of limiting global warming to 2 degrees Celsius above the temperature from 1850, the pre-Industrial Revolution, studies like this suggest that the world such as it is today has already experienced the effects of warming.

“This is another data point for understanding that climate change is a not only a challenge for the future,” Reed said. It’s not this “end of the century problem that we have time to figure out. The Earth has already warmed by over 1 degrees” which is changing the hurricane season and is also impacting other severe weather events, like the heatwave in the Pacific Northwest in 2021. That heatwave killed over 100 people in the state of Washington.

Even being successful in limiting the increase to 2 degrees will create further increases in rainfall from hurricanes, Reed added. As with any global warming research, this study may also get pushback from groups skeptical of the impact of fossil fuel use and more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

Reed contends that this research is one of numerous studies that have come to similar conclusions about the impact of climate change on weather patterns, including hurricanes.

“Researchers from around the world are finding similar signals,” Reed said. “This is one example that is consistent with dozens of other work that has found similar results.”

Amid more warming, hurricane seasons have already changed, which is a trend that will continue, he predicted.

Even on a shorter-term scale, Hurricane Sandy, which devastated the Northeast with heavy rain, wind and flooding, would likely have had more rainfall if the same conditions existed just eight years later, Reed added.

Reed was pleased that Nature Communications shared the paper with its diverse scientific and public policy audience.

“The general community feels like this type of research is important enough to a broad set of [society]” to appear in a high-profile journal, he said. “This shows, to some extent, the fact that the community and society at large [appreciates] that trying to understand the impact of climate change on our weather is important well beyond the domain of scientists like myself, who focus on hurricanes.”

Indeed, this kind of analysis and modeling could and should inform public policy that affects planning for the growth and resilience of infrastructure.

Study origins

The researchers involved in this study decided to compare how the 2020 season would have looked during cooler temperatures fairly quickly after the season ended.

The 2020 season was the most active on record, with 30 named storms generating heavy rains, storm surges and winds. The total damage from those storms was estimated at about $40 billion.

While the global surface temperature has increased 1 degree Celsius since 1850, sea surface temperatures in the North Atlantic basin have risen 0.4 to 0.9 degrees Celsius during the 2020 season.

Reed and his co-authors took some time to discuss the best analysis to use. It took them about four months to put the data together and run over 2,500 model simulations.

“This is a much more computationally intensive project than previous work,” Reed said. The most important variables that the scientists altered were temperature and moisture.

As for the next steps, Reed said he would continue to refine the methodology to explore other impacts of climate change on the intensity of storms, their trajectory, and their speed.

Reed suggested considering the 10 percent increase in rain caused by global warming during hurricanes through another perspective. “If you walked into your boss’s office tomorrow and your boss said, ‘I want to give you a 10 percent raise,’ you’d be ecstatic,” he said. “That’s a significant amount.”

Ecstatic, however, isn’t how commuters, homeowners, and business leaders feel when more even more rain comes amid a soaking storm.