By Daniel Dunaief

Long Islanders are pitching in to protect the people of Madagascar, called the Malagasy, from COVID-19. They are also trying to ensure the survival of the endangered lemurs that have become an important local attraction and a central driver of the economy around Ranomofana National Park.

Patricia Wright, a Distinguished Service Professor at Stony Brook University and founder and executive director of the research station Centre ValBio (CVB), is working with BeLocal to coordinate the creation and distribution of masks. They have also donated soap, created hand washing stations at the local market, and encouraged social distancing.

BeLocal, an organization founded by Laurel Hollow residents Mickie and Jeff Nagel, along with Jeff’s Carnegie Mellon roommate Eric Bergerson, is working with CVB to fund and support the creation of 200 to 250 masks per day. BeLocal also purchased over 1,800 bars of soap that they are distributing at hand washing stations.

All administrators for regional government in the national park area near CVB, which is in the southeastern part of the island nation, have received masks. The groups have also given them to restaurant owners and anybody that handles food, including vendors in the market.

At the same time, CVB has received permission to become a testing site for people who might have contracted COVID-19. At this point, Wright is still hoping to raise enough money to buy a polymerase chain reaction machine, which would enable CVB to perform as many as 96 tests each day.

The non-governmental organization PIVOT, which was founded by Jim and Robin Hernstein, has also helped create screening stations to test residents for fever and other symptoms of the virus. As for the masks, BeLocal and CVB are supporting the efforts of seamstresses, who are working 7 days a week.

Jessie Jordan, a wildlife artist based in Madagascar who has been living at CVB for several weeks amid limited opportunities to return to the United States, has been “busy collaborating with local authorities and contributing masks, soap and hand washing stations to the community.”

At this point, Jordan said people were concerned about the economy, but not as afraid of the virus. “The local health centers are less busy right now because of confinement measures and people are scared of testing positive,” she explained in an email.

The Malagasy who benefit from the national park economically through tours and the sale of local artwork have suffered financially. Social distancing in the cities is “nearly impossible,” while Jordan said she has heard that some people in the countryside don’t have access to TV or radio and are not aware of the situation.

As of last week, Madagascar had 132 confirmed positive cases of the virus. Through contact tracing, the government determined that three people brought COVID-19 to the nation when they arrived on different planes. The country had 10 ventilators earlier this month for a population that is well over 23 million.

BeLocal researched the best material to create masks that would protect people who worked in the villages around Ranomafana. “We researched templates and materials and worked together with CVB to choose the best material that would be available,” Leila Esmailzada, the Executive Director of BeLocal, explained in an email.

BeLocal organized a team that reached out to Chris Coulter, who had started making soap several years ago. Coulter has worked with local officials to make soap.

“We knew Coulter from a few years ago” from an effort called the Madagascar Soap Initiative to get soap into every home and make it accessible, explained Mickie Nagel, the Executive Director of BeLocal. “We hope the people making it right now will consider turning this into a business.” Before Madagascar instituted restrictions on travel, BeLocal and CVB had purchased several sewing machines.

Representatives from BeLocal and CVB have been conducting hand washing and social distance education efforts to encourage practices that will limit the spread of COVID-19. Government officials have also shared instructions on the radio and TV, Wright said. When the mayor of Ranomofana Victor Ramiandrisoa has meetings, everybody stands at least six feet apart.

CVB has produced picture drawings in Malagasy that are plastered on the sides of cars that describe hand washing procedures and social distancing. “We also have educational signs in the post offices, restaurants and in the mayor’s offices that we paid for,” Wright explained. She said the government, CVB and BeLocal are all educating people about practices that can limit the spread of the deadly virus.

“Organizations in Ranofamana are collaborating with the local government on efforts to prevent the spread of COVID-19,” Esmailzada wrote. “The local government recently began conducting PSA’s along the road and in main markets about hand washing, mask wearing and social distancing and CVB staff are leading by example.”

As for the lemurs Wright, whose work was the subject of the Imax film “Island of Lemurs: Madagascar,” said the country has taken critical steps to protect these primates.

“The government of Madagascar is assuming the worst and is not allowing anybody into the park,” Wright said. The president of Madagascar, Andry Rajoelina, has closed national parks to protect the lemurs, Wright said.

The lemurs have the support of conservation leader Jonah Ratsimbazafy, who earned his PhD while working with Wright at Stony Brook University. Ratsimbazafy is one of the founding members of the Groupe d’Etude et de Research sur les Primates, which is a community based conservation organization that protects lemurs.

Wright and others are concerned the virus may spread to lemurs. Several lemurs species have the angiotensin converting enzyme, or ACE2, that forms the primary point of attachment for the virus in humans.

Indeed, scientists around the world are working to find those species which might be vulnerable to the virus. According to recent research preprinted in bioRxiv from a multi-national effort led by scientists at the University of California in Davis, several species of lemur have high overlap in their ACE2 inhibitors. This includes the endangered aye-aye lemur, which is the world’s largest nocturnal primate, and the critically endangered indri and sifaka.

“We are worried that lemurs might get the virus,” Wright said.

Photos courtesy of Jessie Jordan

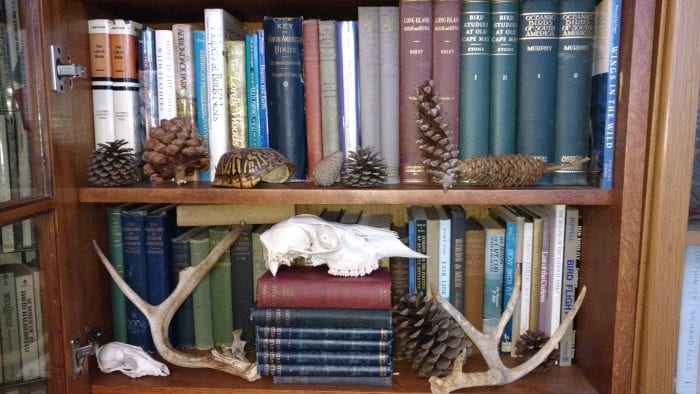

live grey fox, the most recent experience in the autumn two years ago. Spying him before he saw me as I fortuitously was hidden behind a bushy, young Pitch Pine tree, this beautiful grizzled looking animal was patrolling along a sandy trail in the Dwarf Pine Plains of the Long Island Pine Barrens.

live grey fox, the most recent experience in the autumn two years ago. Spying him before he saw me as I fortuitously was hidden behind a bushy, young Pitch Pine tree, this beautiful grizzled looking animal was patrolling along a sandy trail in the Dwarf Pine Plains of the Long Island Pine Barrens.

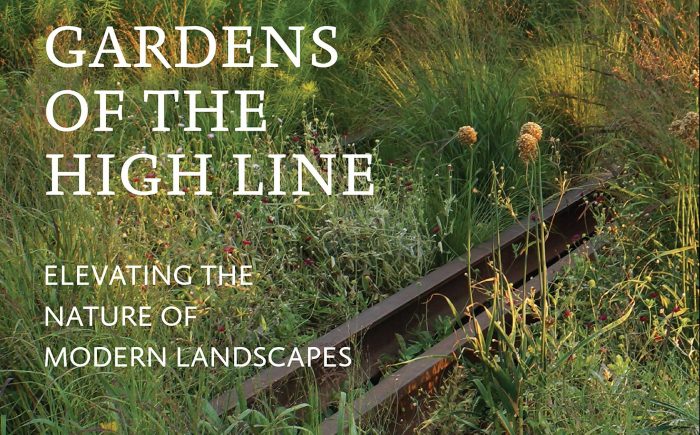

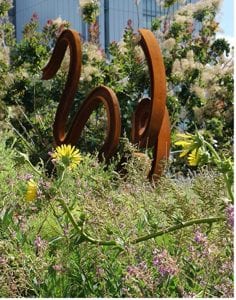

“Though it’s unlikely there will ever be another place quite like the High Line, it offers a wealth of insights and approaches worthy of emulation in gardens large or small, public or private. Authentic in spirit and execution, the High Line’s gardens offer a journey that is intriguing, unpredictable, imperfect, and, above all, transformative.”

“Though it’s unlikely there will ever be another place quite like the High Line, it offers a wealth of insights and approaches worthy of emulation in gardens large or small, public or private. Authentic in spirit and execution, the High Line’s gardens offer a journey that is intriguing, unpredictable, imperfect, and, above all, transformative.”