By Daniel Dunaief

It’s not exactly a Rembrandt hidden in the basement until someone discovers it in a garage sale, but it’s pretty close.

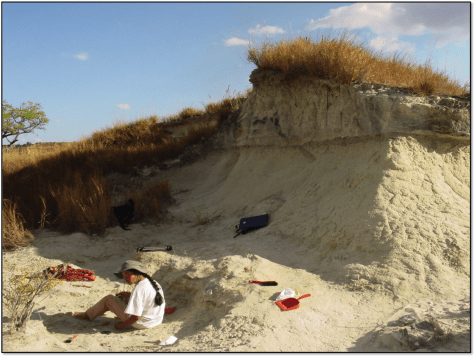

More than two decades ago, a Malagasy graduate student named Augustin Rabarison spotted crocodile bones in northwestern Madagascar, so he and a colleague encased them in a plaster jacket for further study.

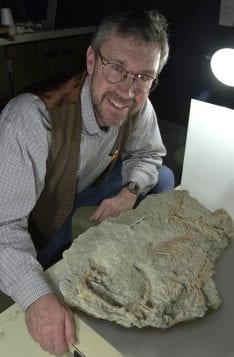

David Krause, who was then a Professor at Stony Brook University and is now the Senior Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science, didn’t think the crocodile was particularly significant, so he didn’t open the jacket until three years later, in 2002.

When he unwrapped it, however, he immediately recognized a mammalian elbow joint further down in the encased block of rock. That elbow bone, as it turned out, was connected to a new species that is a singular evolutionary masterpiece that has taken close to 18 years to explore.

Recently, Krause, James Rossie (an Associate Professor in the Department of Anthropology at Stony Brook University) and 11 other scientists published the results of their extensive analysis in the journal Nature.

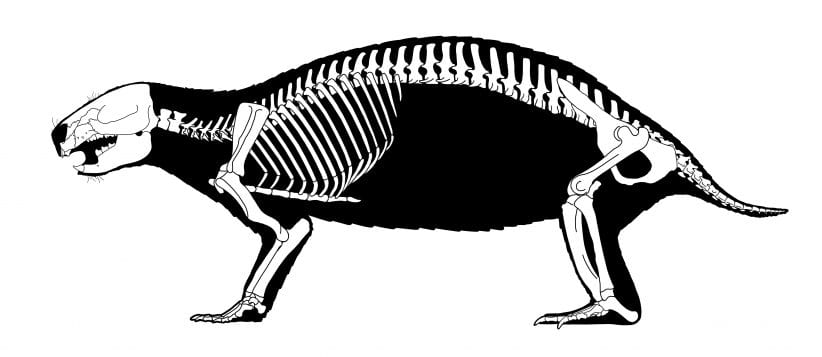

The creature, which they have named Adalatherium hui, has numerous distinctive features, including an inexplicable and unique hole on the top of its snout, and an unusually large body for a mammal of its era. The fossil is the most complete for any Mesozoic mammal discovered in the southern hemisphere.

“The fossil record from the northern continents, called Laurasia, is about an order of magnitude better than that from Gondwana,” which is an ancient supercontinent in the south that included Africa, South America, Australia and Antarctica, Krause explained in an email. “We know precious little about the evolution of early mammals in the southern hemisphere.”

This finding provides a missing piece to the puzzle of mammalian evolution in southern continents during the Mesozoic Era, Krause wrote.

The Adalatherium, whose name means “crazy beast” from a combination of words in Malagasy and Greek, helps to broaden the understanding of early mammals called gondwanatherians, which had been known from isolated teeth and lower jaws and from the cranium of a new genus and species, Vintana sertichi, that Krause also described in 2014.

The closest living relatives of gondwanatherians were a group that is well known from the northern hemisphere, called multituberculates, Krause explained.

The body of Adalatherium resembled a badger, although its trunk was likely longer, suggested Krause, who is a Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus at Stony Brook.

Krause called its teeth “bizarre,” as the molars are constructed differently from any other known mammal, living or extinct. The front teeth were likely used for gnawing, while the back teeth likely sliced up vegetation, which made probably made this unique species a herbivore.

The fossil, which probably died before it became an adult, had powerful hind limbs and a short, stubby tail, which meant it was probably a digger and might have made burrows.

Rossie, who is an expert in studying the inside of the face of fossils with the help of CT scans, explored this unusually large hole in the snout. “We didn’t know what to make of it,” he said. “We can’t find any living mammal that has one.”

Indeed, the interpretation of fossils involves the search for structural and functional analogs that might suggest more about how it functions in a living system. The challenge with this hole, however, is that no living mammal has it.

Gathering together with other cranial fossil experts, Rossie said they agreed that the presence of the hole doesn’t necessarily indicate that there was an opening between the inside of the nose and the outside world. It was likely plugged up by cartilage or other soft tissue or skin.

“If we had to guess conservatively, it would probably be an enlarged hole that allowed the passage of a cluster of nerves and blood vessels,” Rossie said.

That begs the question: why would the animal need that?

Rossie suggests that there might have been a soft tissue structure on the outside of the nose but, at this point, it’s impossible to say the nature of that structure.

The Associate Professor, who has been a part of the research team exploring this particular fossil since 2012, described the excitement as being akin to opening up a Christmas present.

“You’re excited to see what’s in there,” he said. “Sometimes, you open up the box and see what you were hoping for. Other times, you open the box and say, ‘Oh, I don’t know what to say about this [or] I don’t know what I’m looking at.’”

For Rossie, one of the biggest surprises from exploring this fossil was seeing the position of the maxillary sinus, which is in a space that is similar across all mammals except this one. When he first saw the maxillary sinus, he believed he was looking at a certain part of the nasal cavity, where it usually resides. When he studied it more carefully, he realized it was in a different place.

“All cars have some things in common,” said Rossie, who is interested in old cars and likes to fix them. The common structural elements of cars include front and back seats, a steering wheel, and dashboard. With the maxillary sinus “what we found is that the steering wheel was in the back seat instead of the front.”

A native of upstate Canton, which is on the border with Canada, Rossie enjoyed camping growing up, which was one of the initial appeals of paleontology. Another was that he saw an overlap between the structures nature had included in anatomy with the ones people put together in cars.

A resident of Centerport, Rossie lives with his wife Helen Cullyer, who is the Executive Director of the Society for Classical Studies, and their seven-year-old son.

As for the Adalatherium, it would have had to avoid a wide range of predators, Krause explained, which would have included two meat-eating theropod dinosaurs, two or three large crocodiles and a 20-foot-long constrictor snake.

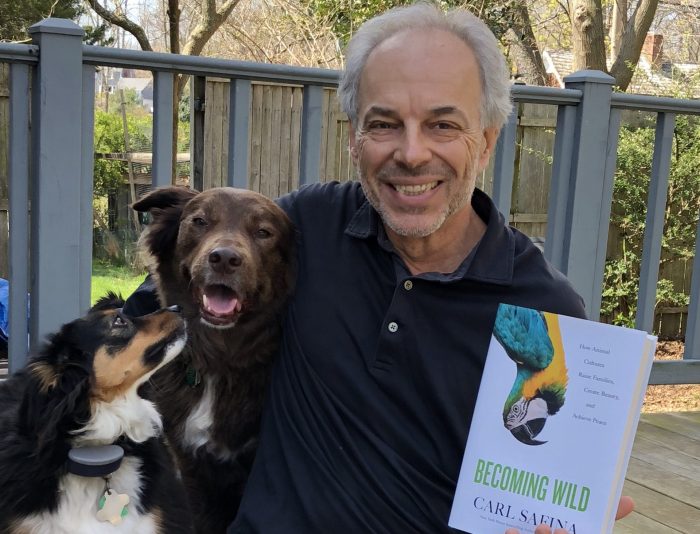

Safina divides the book into the study of sperm whales (families); scarlet macaws (beauty); and chimpanzees (peace). Each of the three sections is rich, detailed and engaging enough to be a book onto itself. He has brought them together under the umbrella of his exploration of culture.

Safina divides the book into the study of sperm whales (families); scarlet macaws (beauty); and chimpanzees (peace). Each of the three sections is rich, detailed and engaging enough to be a book onto itself. He has brought them together under the umbrella of his exploration of culture.

The idea culminated into what she calls the “Be Kind Movement,” where individuals can come up to a table in front of the Village Center, pick out a rock, take it home and paint a message of hope, kindness or a fun design. Once they are done painting his of her rock, Orifici said they can place their rock in the designated “Kindness Garden” located behind the Long Island Explorium at the Children’s Park off East Broadway.

The idea culminated into what she calls the “Be Kind Movement,” where individuals can come up to a table in front of the Village Center, pick out a rock, take it home and paint a message of hope, kindness or a fun design. Once they are done painting his of her rock, Orifici said they can place their rock in the designated “Kindness Garden” located behind the Long Island Explorium at the Children’s Park off East Broadway.