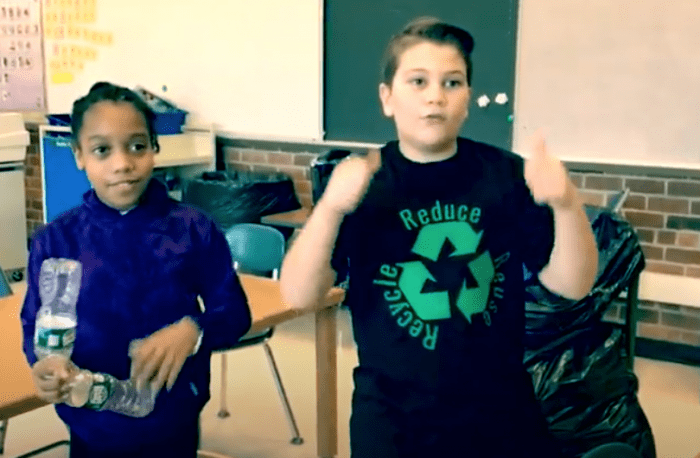

PSEG Long Island has announced the winners of its first-ever Earth Day Video PSA Contest. Two hundred seven videos were submitted by creative, local schoolchildren, and 10 made the final cut. Dozens of students and teachers who participated in the program watched the announcement live via webinar hosted by the company on April 22.

Over the past two and a half months, nearly 4,500 students in grades 4-8 engaged in the I AM EM-Powered Program and Student Challenge. Created by educational consultants, D. Barrett Associates, the STEM-related coursework provided lessons on energy conservation, energy efficiency and renewable energy in alignment with current educational standards on these topics. The curriculum was also tailored for classroom, virtual learning and hybrid scenarios. Teachers could select and submit their favorite three videos to be judged by a strict grading rubric.

“It was so exciting to see these award-winning videos and to announce the 10 winners today,” said Suzanne Brienza, PSEG Long Island’s director of Customer Experience and Utility Marketing, who co-hosted the event. “The students’ messages of protecting our oceans, conserving electricity and using energy efficient light bulbs are lessons for all of us.”

Michael Voltz, PSEG Long Island’s director of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, also co-hosted the event. “It’s great to see how these young environmental advocates are embracing these important issues and adding to the discussion about what we can do to protect and nurture our planet,” he said. “We are very pleased with the positive feedback from students and teachers about this new I AM EM-Powered Program and Student Challenge for Earth Day. Congratulations to all of the students who participated, and thank you to all the teachers who implemented the coursework.”

Sponsored by PSEG Long Island, the I AM EM-Powered Program and Student Challenge was provided free to students in the company’s service area – Nassau and Suffolk counties and the Rockaways.

Here is a complete list of the winners.

| Student Winners | Name of

PSA video |

Grade | Teacher(s) | School | District |

| Pavly Zaky | Lilly Knows LEDs | 6th | Karen Alonge | East Meadow Middle School | East Meadow |

| Jacob Park

Dylan Couture Josh Bonfanti |

Conserving Energy | 7th | Ellen McGlade-McCulloh | East Meadow Middle School | East Meadow |

| Juliette Markesano | 5 Easy Ways to Save Money | 6th | Karen Alonge | East Meadow Middle School | East Meadow |

| Michael Gallarello Jayleen Martorell | Put Your Waste in its Rightful Place | 5th | Veronica Weeks Tara Dungate |

Bretton Woods Elementary School | Hauppauge |

| Valerie Tuosto

Zia Baluyot |

Cleaner Energy is Your Superpower | 8th | Matthew Schneck | Lynbrook South Middle School | Lynbrook |

| Nicole Marino Clara Levy Brooke Marek Leah Anzalone | Energy Conservation | 7th

|

Vince Interrante | Mineola Middle School | Mineola |

| James Catania

Jose Velasquez |

Save Water | 8th | Lisa McDougal | Oyster Bay High School | Oyster Bay-East Norwich |

| Skyler Placella | Special Energy Agent | 5th | Diana Hauser | James H. Vernon School, Oyster Bay | Oyster Bay-East Norwich |

| Abigail Rudnet | How to Conserve Energy | 5th | Frank Sommo | James H. Vernon School, Oyster Bay | Oyster Bay-East Norwich |

| Lena Okurowski

Sophia Lastorino Layla Kelly |

Save the Oceans | 5th | Justin DeMaio | Bayview Elementary School | West Islip |

The 10 award-winning videos are available for viewing at youtube.com/psegli. Click the playlist titled “I Am EM-powered PSA contest winners 2021.”

PSEG Long Island provides educational resources through its robust Community Partnership Program, which includes several educational programs for children of all ages at schools, after-school and camp programs. These shows and programs on energy conservation, electric safety and preparing for an emergency have educated tens of thousands of children. This new I Am EM-Powered coursework and contest has been receiving high praise since it was added to the educational programming lineup.

Each will speak differently to the individual viewer. On a personal level, these moments demand attention:

Each will speak differently to the individual viewer. On a personal level, these moments demand attention:

But it’s live oak leaves, Tallamy explains, where the value of oaks come into full focus. More than 500 species of butterflies and moths feed on oak leaves, including many geometrid caterpillars (or inchworms as we learned in our childhoods). Many hundred more other insect species eat oak leaves (or tap into the sap of oaks too), including leafhoppers, treehoppers, and cicadas, among others. These leaf-eating species, in turn, sustain many dozens of songbird species we love to watch — warblers, orioles, thrushes, wrens, chickadees, grosbeaks and more.

But it’s live oak leaves, Tallamy explains, where the value of oaks come into full focus. More than 500 species of butterflies and moths feed on oak leaves, including many geometrid caterpillars (or inchworms as we learned in our childhoods). Many hundred more other insect species eat oak leaves (or tap into the sap of oaks too), including leafhoppers, treehoppers, and cicadas, among others. These leaf-eating species, in turn, sustain many dozens of songbird species we love to watch — warblers, orioles, thrushes, wrens, chickadees, grosbeaks and more.

“It’s hard to study climate change and aspects of climate change and be a mother because the data’s very real to you,” said Dr. Emily Fischer, atmospheric chemist and associate professor in the Department of Atmospheric Science at Colorado State University. “We need a massive shift in the way we produce energy within 10 years, the same time period I need to save and plan to send my daughter to college. We’re hoping moms will realize climate change impacts their children and that we have solutions, but we need to act relatively quickly.”

“It’s hard to study climate change and aspects of climate change and be a mother because the data’s very real to you,” said Dr. Emily Fischer, atmospheric chemist and associate professor in the Department of Atmospheric Science at Colorado State University. “We need a massive shift in the way we produce energy within 10 years, the same time period I need to save and plan to send my daughter to college. We’re hoping moms will realize climate change impacts their children and that we have solutions, but we need to act relatively quickly.”