Stony Brook University has been at the center of the COVID-19 pandemic, as hospital staff has treated and comforted residents stricken with the virus and researchers have worked tirelessly on a range of projects, including manufacturing personal protective equipment. Amid a host of challenges, administrators at Stony Brook have had to do more with less under budgetary pressure. In a two-part series, Interim Provost Fotis Sotiropoulos and President Maurie McInnis share their approaches and solutions, while offering their appreciation for their staff.

Part I: Like many other administrators at universities across the country and world, Fotis Sotiropoulos, Dean of the College of Engineering and Applied Sciences and Interim Provost of Stony Brook University, has been juggling numerous challenges.

Named interim provost in September, Sotiropoulos, who is also a SUNY Distinguished Professor of Civil Engineering, has focused on ways to help President Maurie McInnis keep the campus community safe, keep the university running amid financial stress and strain, and think creatively about ways to enhance the university’s educational programs.

Stony Brook University which is one of two State University of New York programs to earn an Association of American Universities distinction, is in the process of developing new degree programs aimed at combining expertise across at least two colleges.

“We have charged all the deans to work together to come up with this future-of-work initiative,” Sotiropoulos said. “It has to satisfy a number of criteria,” which include involving at least two colleges or schools and it has to be unique. Such programs will “allow us to market the value of a Stony Brook education.”

Sotiropoulos said Stony Brook hoped that the first ideas about new degrees will emerge by the middle of January.

Under financial pressure caused by the pandemic, the university has “undertaken this unprecedented initiative to think of the university as one,” Sotiropoulos said. Looking at the East and West campus together, the university plans to reduce costs and improve efficiency in an organization that is “complex with multiple silos,” he said. At times, Stony Brook has paid double or triple for the same product or service. The university is taking a step back to understand and optimize its expenses, he added.

On the other side of the ledger, Stony Brook is seeking ways to increase its revenue, by creating these new degrees and attracting more students, particularly from outside the state.

Out-of-state students pay more in tuition, which provides financial support for the school and for in-state students as well.

“We have some room to increase out-of-state students,” Sotiropoulos said. “There is some flexibility” as the university attempts to balance between the lower tuition in-state students pay, which benefits socioeconomically challenged students, and the higher tuition from out-of-state students.

While the university has been eager to bring in talented international students as well in what Sotiropoulos described as a “globally-connected world,” the interim provost recognized that this effort has been “extremely challenging right now,” in part because of political tension with China and in part because Chinese universities are also growing.

Stony Brook “recognizes that it needs to diversify right now. The university is considering strategies for trying to really expand in other countries. We need to do a lot more to engage students from African countries,” he said.

Sotiropoulos described Africa as an important part of the future, in part because of the projected quadrupling of the population in coming decades. “We are trying to preserve our Asian base of students,” he said, but, at the same time, “we are thinking of other opportunities to be prepared for the future.”

While the administration at the university continues to focus on cutting costs, generating revenue and attracting students to new programs, officials recognize the need to evaluate the effectiveness of these efforts for students. “Assessment is an integral part,” Sotiropoulos said. The school will explore the jobs students are able to find. “It’s all about the success of our students,” he added. The school plans to assess constantly, while making adjustments to its efforts.

Pandemic Response

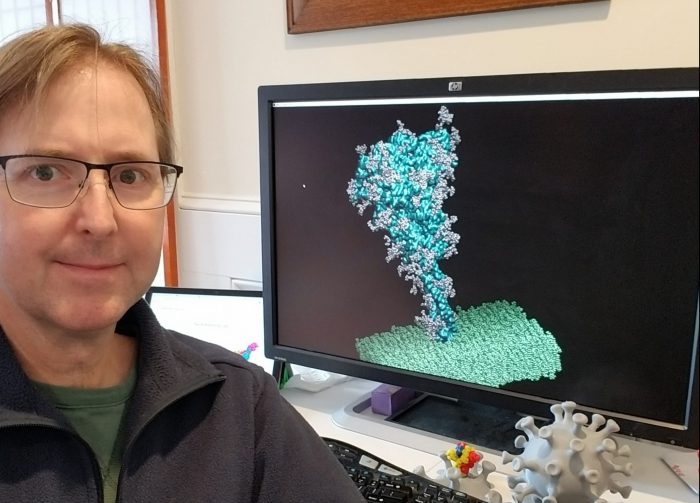

Stony Brook University has been at the forefront of reacting to the pandemic on a number of fronts. The hospital treated patients during the heavy first wave of illnesses last spring, while the engineering school developed ways to produce personal protective equipment, hand sanitizer, and even MacGyver-style ventilators. The university has also participated in multi-site studies about the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19.

Stony Brook has been involved in more than 200 dedicated research projects across all disciplines, which span 45 academic departments and eight colleges and schools within the university.

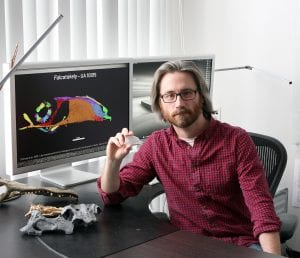

Sotiropoulos, whose expertise is in computational fluid mechanics, joined a group of researchers at SBU to conduct experiments on the effectiveness of masks in stopping the way aerosolized viral particles remain in the air, long after patients cough, sneeze, and even leave the room.

“Some of these droplets could stay suspended for many minutes and could take up to half an hour” to dissipate in a room, especially if there’s no ventilation, Sotiropoulos said, and added he was pleased and proud of the scientific community for working together to understand the problem and to find solutions.

“The commitment of scientists at Stony Brook and other universities was quite inspirational,” he said.

According to Sotiropoulos, the biggest danger to combatting the virus comes from the “mistrust” of science, He hopes the effectiveness of the vaccine in turning around the number of people infected and stricken with a variety of difficult and painful symptoms can convince people of the value of the research.

Sotiropoulos said the rules the National Institutes of Health have put in place have also ensured that the vaccine is safe and effective. People who question the validity of the research “don’t understand how strict this process is and how many hurdles you have to go through.”

Part 2 will appear in next week’s issue.