By Daniel Dunaief

While one bad apple might spoil the bunch, the same might be true of one bad cancer gene.

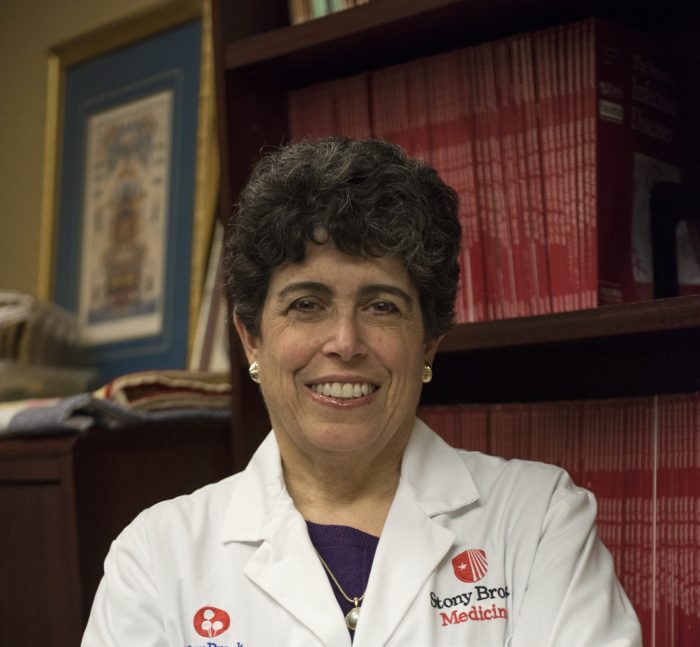

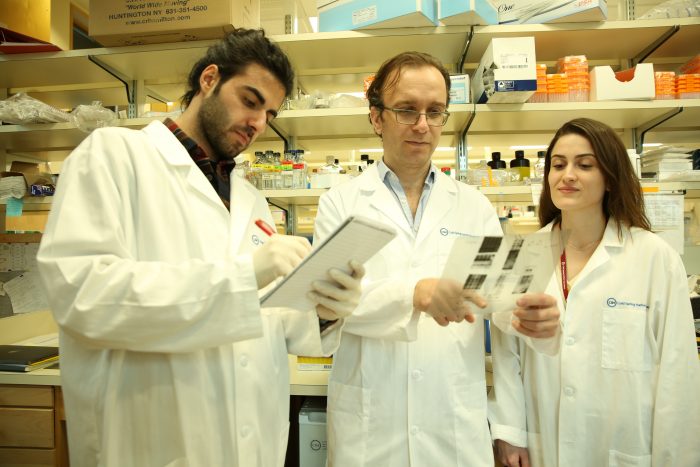

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory’s Cancer Director Dave Tuveson and Derek Cheng, who earned his PhD from Stony Brook University while conducting research in Tuveson’s lab, recently explored how some mutant forms of genes in pancreatic cancer can involve other proteins that also promote cancer.

A gene well-researched in Tuveson’s lab, mutated KRAS promotes cell division. Mutant versions of this gene continue to produce copies of themselves, contributing to cancer.

Turning off or blocking this gene, however, doesn’t solve the problem, at least not in the laboratory models that track a cancer cell’s response.

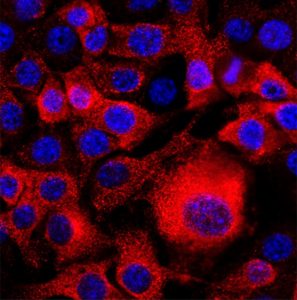

In laboratory models of pancreatic cancer, a disease for which the prognosis is often challenging, other proteins play a role, creating what researchers call an “adaptive resistance” to chemotherapy.

In a paper published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Cheng, who is the first author and is currently in his final year of medical school at the Stony Brook Renaissance School of Medicine, and Tuveson showed that a protein called RSK1 interacts at the membrane with mutated KRAS. When KRAS is inhibited, the RSK1 protein, which normally keeps RAS proteins dormant, becomes more active.

“If you antagonize KRAS, you would get a rebound” as the cancer cells develop a resistance to the original drug, Tuveson said. “We found a feedback loop.”

The research “focused on identifying protein complexes with oncogenic KRAS that would potentially be relevant in pancreatic cancer,” Cheng explained in an email. “My work suggests that an RSK1/NF1 complex exists in the vicinity of oncogenic KRAS.”

While Cheng was able to show that the role of membrane-localized RSK1 provided negative regulation of wild-type RAS, it “remains to be studied what the role of the RSK1 at the membrane [is] in the context of oncogenic KRAS.”

KRAS is a molecular switch that turns on and off with the help of other proteins. With certain mutations, the switch doesn’t turn off, continuing to signal for copying and dividing, which are hallmarks of cancer cells. With specific activating mutations, the switch can lose its ability to turn off and constitutively signal for proliferation, metabolic reprogramming, and other behaviors characteristic of cancer cells, Cheng explained.

A cell with an oncogenic KRAS has the tendency to be more fit than a normal cell without one. Such cells will likely grow at a faster rate under stressful conditions, which, over time, can enable them to outcompete normal cells, Cheng continued.

When KRAS is in an oncogenic state, another protein, called RSK1 is hanging around the membrane. RSK1 has several functions and can participate in numerous cellular signaling pathways.

While RSK1 is involved in protein translation by phosphorylating S6 kinase, it also has other functions at the plasma membrane, where it shuts down wild type RAS proteins.

Other researchers have suggested a negative feedback for RSK1 and NF1.

“Our contribution demonstrated some relevance of this interaction in pancreatic cancer cells,” Cheng explained in an email.

Cheng said RSK is known to have various effects, depending on the context. In the paper, the scientists showed that RSK has a “negative feedback properties, such as that, upon the removal of mutant KRAS, it has this negative regulatory role.”

Graduate student Sun Kim and post doctoral researchers Hsiu-Chi Ting and Jonathan Kastan are currently exploring whether RSK has a pro-oncogenic function on the membrane in the tumor cell.

So far, these studies suggest that while a direct inhibitor against oncogenic KRAS would likely be the greatest target for an effective therapy, cancer cells may still be able to use signals from other RAS isoforms.

“A combination of targeting KRAS and modulating regulators of RAS such as RSK1/NF1 and SOS1 may enhance therapeutic efficacy,” Cheng suggested.

Cheng is grateful for the opportunity to learn from numerous Tuveson lab members on ways cancer cells differ from healthy cells.

The discovery of the potential roles of RSK1 in cancer provides some possible explanation for the potential resistance mechanisms of mutant KRAS inhibitors.

While he was encouraged that a prestigious journal published the research, Tuveson said he hopes this type of observation “will lead to something that will be useful for a pancreatic cancer patient and not just” provide compelling ideas.

Cheng attended medical school for two years before joining Tuveon’s lab for the next six years.

Cheng defended his thesis in 2020 during the pandemic on a zoom call.

“I was one of the first people to defend with this format for both CSHL and SBU,” Cheng explained. “I was able to invite many friends and family that probably would not have been able to make the trip.”

Cheng’s family has battled cancer, which contributed to his research interests.

When he was an undergraduate, he had an uncle develop glioblastoma, while another uncle and his grandfather developed colon cancer.

“I knew I wasn’t going to be able to do much about their medical condition, but I wanted to work on something that people cared about,” Cheng explained.

Outside of the lab, Cheng enjoys working on his car and his motorcycles. He feels a sense of autonomy working on his own projects.

He’s most proud of a motorcycle for which he rebuilt the front end with parts from another model to outfit a larger brake system.

A native of St. Louis, Cheng is a fan of the hockey team, the Blues. He owns a game-worn jersey from almost every member of the 2019 cinderella team that won the Stanley cup, with some of those jerseys coming from Stanley Cup final games.

Cheng plans to apply to residency in internal medicine this year because he wants to continue applying what he learned in his scientific and medical training.

The clinical work reminds him to treat patients and not just the tumors, while scientific research trained him to loo at evidence and literature carefully to find clinical gaps, he explained.